PURPOSE OF THIS ARTICLE

This article will translate the entire fresco on the large panel in the Marsoulas cave using the proto-Sumerian ideographic language and its associated languages, Sumerian and hieroglyphic. This article is one of ten deciphering examples taken from the book “Deciphering the language of caves” that illustrate in concrete terms the fact that the pairs of animals and signs identified by archaeologists and dated to the Upper Palaeolithic actually correspond in every respect to the protosumerian ideographic language, the oldest known ideographic language.

Table of contents

LINK THIS ARTICLE TO THE ENTIRE LITERARY SERIES “THE TRUE HISTORY OF MANKIND’S RELIGIONS”.

This article is an excerpt from the book entitled :

THE DECIPHERING OF CAVE LANGUAGE

You can also find this book here :

Books

To find out why this book is part of the literary series The True Stories of Mankind’s Religions, go to page :

Structure and content

I hope you enjoy reading this article, which is available in its entirety below:

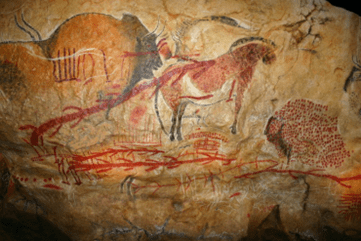

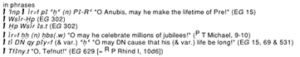

Marsoulas cave: The large panel fresco

Let’s turn now to the signs in the Marsoulas fresco.

Here’s the image as a reminder:

http://prehistoart.canalblog.com/archives/2009/11/01/15639490.html

We’re going to look at several obvious signs:

- The two curved horns

- The “pettiforme” (on the auroch’s flank)

- The pettiforme under the auroch

- The multiple T-signs on the auroch’s body

- Branch signs

- The tectiforme under the horse

- Speckled bison (speckles and clouds of dots)

The sign of two parallel, angled horns

Evidenciation

https://www.creap.fr/pdfs/CFGT-Marsoulas-DARCH2007.pdf

The way in which the fresco is depicted, with the ibex obliterated, serves above all to highlight its two horns

They echo those of the bison

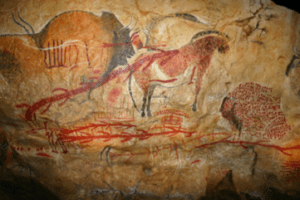

hieratic contribution

This perfectly echoes the fact that ideographic, cuneiform and hieroglyphic scripts are schematic simplifications of more complex figures.

This was already demonstrated in Champollion’s time with hieratic, which was a simplification of the more complex hieroglyphs, taking only the most significant element of the hieroglyph to recall it:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hieratique.png

So, let’s continue to follow in his footsteps if you don’t mind and see what those two curved parallel horns mean:

Meaning

The meaning of the logogram A in Proto-Cuneiform and Sumerian

The fact is that is an absolutely elementary sign in proto-cuneiform.

It’s the first of the signs, so classified in our alphabetical order, since it transliterates as “a”.

It is first on page 1 of the proto-cuneiform sites referenced by the CNIL[1] .

You don’t have to be a graduate of Saint-Cyr to observe it. All it takes is the intellectual will to think outside the box.

This sign is the counterpart of the Greek Aleppo, the Arab alif, the Egyptian vulture A… [2]

But what does “a” mean?

As we have already seen and said, “a” notably means “father“; “a” (or e4) designates a father (and also water, stream, channel, flood, tears, seminal fluid, offspring, father)[3] .

Even if the two parallel broken lines (131) visually evoke a canal, a watercourse, suggesting that this is its primary meaning, its only literal and therefore unique meaning, it’s important to understand that its other sumerian and therefore symbolic meaning is far more important, since it’s that of “father”.

Then, that simple “a” on the bison’s spine tells us that it’s a representation of the father.

Moreover, the associated notions of water and seminal fluid generating offspring convey the imagery of a father, a fertile progenitor.

Note in passing that the parallelism of the two horns or strokes and their break making them skewed are very characteristic and make this sign a complex one, and not a simple sign like a circle, square or simple rectangle.

À = aka = ugu le procreator generator

Since I’m talking about a progenitor, it turns out that “ a5” is also synonymous with “aka”[4] .

Now, if aka means “to do, to act”[5] its homophone “a-ka” means a genetic and biological procreative ancestor.

Indeed, to “a-ka” the Sumerian lexicon Halloran refers us to “úgu“[6] whose homophone ugu4 has the ideogram “ku”. A strict equivalent of “a-ka” is “ a-ugu4“, which also has the ideogram “ku” and means “the father who begat someone”[7] .

I’ve already explained that ku means genetic and biological (male or female) progenitor ancestor.

aa the father

As for “aa” [i.e. “a“, redoubled], it only means “father”[8] .

In other ideographic reference languages

In hieroglyphic

Substitute for a divinity

In our analysis of the sign opposite the auroch in the Lascaux unicorn fresco, we have already seen the significance of simple lines.

I invite you to reread this section to refresh your memory.

With regard to the two simple oblique or inclined lines, we have seen that they illustrate the same aspect that we have already mentioned: the fact that they serve as substitutes for the representation of deities.

Indeed, we have seen[9] that :

- In some cases,

replaces human representations considered magically dangerous, such as the hieroglyphic

replacing

, all of which are vocalized Axt(i) and designate “the two glorious ones”. These “two glorious women” allude to Nekhbet and Ouadjet, the vulture and snake goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt.

- The hieroglyph Axt

is also the name of the goddess Akhet, and the hieroglyph Axt

refers to the king’s tomb as an inhabitant of the horizon[10] , to which it should be added that Axty

an “inhabitant of the horizon” is in fact an epithet of the god[11] .

We thus understand that this sign of two inclined or vertical lines designates a major divinity, a god-king, or a goddess-queen, or even two.

To this we can now add two further considerations:

The meanings of the Y pronunciation in hieroglyphic, demotic (and Sumerian) languages

The first is that the two strokes or

also correspond to the hieroglyph

the double i[12] which transliterates into Y. They therefore also correspond to the Y.

In this case, the Y is a sign of duality.

And we’ve already mentioned that the father of gods is a double god, one of whose variations will be his twin representation of man and beast.

Moreover, is also used in the hieroglyph for rwty

or

which designates the god Routy, the double lion god, who corresponds to the two twins Shou (Sw) and Tefnout (tfnt).[13]

There’s no doubt, therefore, that this sign is used in particular to designate a twin deity.

As regard Demotic language, as we saw in our analysis of the auroch in the Lascaux unicorn fresco, the pronounced Y is written

in Demotic.

It has the sense of “me, I”, which also introduces a magical name of divinity.

And in the form pronounced yA, Ay or hy, it means “to praise”.

Finally, in Sumerian, as the hieroglyphic i is equivalent to A, this Y is a Sumerian double a: a-a, and therefore refers in Sumerian to the same meaning of “father” we have already seen.

These three readings are therefore profoundly complementary, bringing us back to the imagery of a divinized father and/or divine father who must be praised, whose name must not be spoken, a double god who can be represented in twin animal form.

Association with pAty

We’ve just seen that the hieroglyphs of the two strokes or

are pronounced Y.

However, this sign does not occur very often and is found, undoubtedly, not by chance, in the hieroglyphs pAtyw or pAty

or paty

, which designate… a primordial god.

And pAti means a man from an old family…[14]

The associated pAwt pAt

hieroglyphs signify primitive times…[15]

I don’t think I then need to draw you a picture to explain to you to whom this sign or refers…

It’s a good thing too, because while I’m not too bad at deciphering ideograms, I’m not so good at making them on my own!

Since we’re talking about pAti, the primordial god-man, I’d like to draw your attention to the fact that this word breaks down into pA-ti which, in Sumerian, means the father “pa” of “ti”.

We’ll have ample opportunity to see in part 3 of this great volume 2 who is ti… and therefore why the father of the gods was, among other names, also called in this way.

In proto-Elamite

These two simple parallel features are also found in proto-Elamite: or

(M9). [16]

Even if this script has not been translated, it is almost certain that this sign has the same meaning as in proto-Cuneiform (given the close temporal, cultural and geographical proximity between Sumer and Elam), even if it is not necessarily pronounced the same way.

Linear Elamite

These two simple parallel lines are also found in linear Elamite: or

According to the syllabary established by de F.Desset[17] it transliterates zu.

It is then interesting to turn to Sumerian to determine the meaning of zu.

As it happens, zu is equivalent to sú and both mean[18] wisdom, knowledge. The same equivalence also applies to zú and su11 (with the proto-Cuneiform ideogram KA), both of which mean teeth[19] .

This zu/su equivalence is important, as we’ll see in part 2 from God to Adam how this logogram su is important and also relates to primordial man.

Proto-Indian

These two simple parallel strokes are also found in Proto-Indian: or in the form

.

Even if this script has not been translated, it is almost certain that this sign has the same meaning as in proto-cuneiform (given the proximity in time and geography between Sumer and the Indus), even if it is not necessarily pronounced the same way.

Ossécaille

Note the ideographic proximity between the Sumerian sign for a water[20] and the Chinese shui

sign water, with its characteristic central line break evoking a watercourse.

Hittite

Finally, if we turn to hieroglyphic Hittite, we find a meaning that complements everything we’ve looked at, since the signs or

or

designate… a watercourse.

It’s clear, then, that this sign is connected to proto-cuneiform, where it originally signified a channel.

But as we’ve seen and understood, it doesn’t just have this literal meaning: it also means a father, and in the sacred language it designates, to use the Greek expression, the “alpha father”, the primordial father deified as father of the gods after his death.

Hence the fact that in Hittite, the sign vocalized as “i” or “ia” is translated into Latin as “solium”, meaning…?

The high throne (of magistrates, kings and gods); supreme power, majesty…! [21]

…a further confirmation of everything we’ve said above.

I’ll just add that the fact that the watercourse sign is vocalized “i” in hieroglyphic Hittite is pure Sumerian, because “i” in Sumerian, by i7, also means a watercourse, a canal, a river[22] ; and in Sumerian too ia is an equivalent of i[23] !

Conclusion on the meaning of these two curved parallel “horns”: a(d)am

I sincerely believe that, having covered all ideographic languages, starting with proto-cuneiform and ending with hieroglyphic Hittite, we’ve come full circle, and that the meaning of this double stroke couldn’t be clearer.

It’s clear that the sound “a”, probably the first sound uttered by any being and which became the first letter of our alphabet, referred in proto-cuneiform directly to the primordial father who became the supreme father of the gods. Even if in another form, this sign when coupled with the bison in the Marsoulas cave, just like the sign

coupled with the auroch in the Lascaux unicorn panel, can just as easily be read:

“adam(a)” since a is equivalent to “ad(a) / a-aa,” and “auroch” “áma/am” is equivalent to “bison” “alim“.

The pettiform

Let’s move on to the analysis of the pettiform on the bull’s flank:

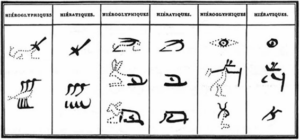

Evidenciation

Large painted panel. Detail of the series of inverted-T signs painted in violet and red on the large buffalo. The two signs on the right have been misinterpreted as a claviform. © C. Fritz and G. Tosello

https://www.creap.fr/pdfs/CFGT-Marsoulas-DARCH2007.pdf ; p.26

While the orange signs on the right can be thought of as 3 inverted T-signs, the sign on the left is clearly made from a single block.

Note, then, that although André Leroi-Gourhan describes it as a pettiforme with straight teeth in his representation :

.

(Unless you consider that this tooth is attached to the rest without being an integral part of it, in which case the sign would be

) this sign in its complete form is then:

.

Admittedly, this is a very special form.

Meaning

It is less so when compared with the following proto-Cuneiform: šu or tak

…

To understand what this ideogram means, let’s first look at what šu means:

Su in Sumerian (pronounced shou)

This logogram has several very important meanings. I will mention here the main ones in relation to what we are dealing with:

The hand as a symbol of royal, divine, Christ-like domination

šu refers directly and literally to a hand[24] and also to notions of controlling force[25] . šu therefore refers to a strong, controlling hand.

This refers to the idea of domination by a powerful person, a ruler, a god.

This notion of domination and royalty is reinforced by the fact that šu by šuš2,3 also has the meaning of anointing[26] , being a contraction of “body” (su) and the verb “to anoint” (eš).

But being anointed was the privilege of kings and gods.

We can also say “Christs” since “Christ” means “anointed”[27] .

šu is therefore potentially a king, a god, a christ.

A woodcutter hand

One of the actions of this hand was to fell one or more trees, since šu by šuš4 means to fell trees, whose homophone is šuš2, šu2,4, which generally means “to overturn, to fell, to make dark, to cover (the sun) with one’s hand”[28] .

Later in the series, we’ll see why the father of the gods was depicted as a woodcutter.

Praying to a god who is a source of blessings

šu also carries the idea of praying[29] (literally, “to greet, to hail, to acclaim” with the hand). Which, of course, is synonymous with the presence of a deity.

Seeing this sign implied that worshippers of this god prayed to him for his blessing.

Man at the foundation of the world

šu carries with it the idea of primordial man, at the foundation of the world.

Indeed, šú means to sit, to reside, being the contraction of “su” “body, substitute, replacement” and “uš8″ “foundation, base”[30] .

Thus, šu is a contraction of su-uš. It therefore includes their respective meanings.

We’ll see in Part II why “su” is one of the logograms that designates primordial man. And what exactly the notion of substitute refers to in his case.

We’ll also see that the logogram uš (or us) designates him as man, the primordial progenitor (generally presented in the ithyphallic position) (uš is a man and a phallus[31] ), the founder of the world or the man at the foundation of the world (ús, uš, or uš8 mean foundation), a total man (ús, úz), a dead man (uš), a model of wisdom, discernment, intelligence, reflection, decision (uš5).

A twin

You may have noticed that one of the meanings of šu in addition to the hand is also a part, a portion[32] .

You’ll no doubt recall that in our explanation of maš, we saw that it designates a half, a twin[33] which etymologically in Sumerian translates as someone who leaves, goes out ma4 with a portion šè, meaning who comes out (from the mother’s womb?) with a share of his twin brother.

So, because šu is also a part, a portion, it’s an equivalent of maš and therefore also a twin (and also a star, as we’ll see later).

We can also add that since šu includes uš, these two “words” are etymologically “twins” and just as uš designates primordial man, šu is his mirror word, his mirror animal under šu the wild bull.

And šu must refer to a wild bull.

That’s what we’re going to see now:

The bull procreator, the bull man

In this paragraph, we’ll understand that just as the two parallel horns and the bison form the word ad(a)am(a), the father (ad(a) – bison/auroch/bull (áma/am),

the šu sign with the bison also forms the equivalent words :

- ku- (u)šu the biological procreative ancestor ku the wild bull (u)šu

- gu-uš the ox gu the primordial man uš

ku- (u)šu

The hand and its fingers, the ox and its horns

We will see that am (the wild bull) is equivalent to šu :

To see this, note that while the hand is said “šu“, the fingers are said šusi, literally, “the horns, the rays of the hand”, as “si” means “horns, rays, antennae”.

Note that an elephant is called “am-si“, which literally translates as “wild ox” with “horns”.

The fact that the hand symbol is here applied to the wild bison-bull suggests that the two are closely linked.

As a result, the hand šu-si is potentially equivalent to am-si and therefore šu = am.

šu must be able to designate a wild bull alone and directly, just like am

The hand and the elephant vs. the star

In passing from this explanation, please note that the hand is associated with a star, since the fingers are synonymous with rays. Thus, one of the symbolic meanings of the hand is that it represents a star.

Similarly, horns are also synonymous with rays. Since the hand is an etymological and symbolic equivalent (šu-si = am-si) of the bull with horns, the elephant (and the mammoth), it follows that the latter are also synonymous with the star.

Given that the star is an emblematic symbol of the great divinity, as we’ve already seen in part (review the explanation of the meaning of the maš cross), so the hand, like the elephant, the mammoth, the ox with horns, the buffalo, the bull represents beings that have become stars, divinities in the afterlife, or even the great divinity itself.

kušu(m)

But let’s return to the equivalence šu = am, to the etymological demonstration that šu also designates a bovid.

It is interesting to note that kušu (or kušum) refers, among other things, to a herd of cattle[34] .

However, in these words it is the term šum or šu that carries the idea of bovid.

Indeed, “sún” designates “an auroch cow, a wild cow”[35] and “šum” and “sun” are presented as equivalents[36] [concerning the association between the wild cow and the star, note that šún[37] is a star…; this only confirms that the horned bovid is a star, a divinity; obviously, the archaic origin of the English word “sun” for sun is illuminated in a new light].

“šum” therefore designates “a wild ox” and probably ušum in the sense of “ruler, (god) sun of the cow auroch, of the wild cow”.

Another meaning of ušum is “solitary”, which refers to the great deity defined as unique, alone, solitary.

So what does kušu or kušum mean?

Meaning of ku

We know that the term “ku” designates a biological procreative ancestor, male or female.

From then on, kušu or kušum means ku the biological procreative ancestor ušu(m) the solitary bovid

We can also note that the term kušum is, according to the lexicon, a contraction of ki (place) and ušum (solitary)[38] .

But, as we understand it, it can also and above all mean the solitary wild ox ušum of the Earth ki (because ki means Earth in Sumerian[39] ) or of the Earth goddess (Ki being the Sumerian name of the Earth goddess).

ušum the dragon and the ox

Note then that the fact that (u)šum designates a wild ox explains one of the meanings of ušum, ušu which also designates a dragon.

Indeed, according to the Halloran lexicon, ušum the dragon is the contraction of uš11, “snake venom” and “am, “wild ox”; in other words, a dragon is literally a wild ox with snake venom[40] .

But we can also consider two three things:

- If the wild ox is only said šum or šu, then the dragon is the ruler, the “sun” “u” of the ox šu(m).

- If wild ox is also said ušum or ušu (this is perfectly possible, as ù-sun is given as the equivalent of sún for wild cow[41] ) then it is strictly equivalent to the word dragon.

- Or both

These different explanations are interesting, as they show us that ušum the dragon conveys several double meanings: he is both the leader of the wild ox and at the same time the serpent-dragon who bit him, and at the same time he is potentially a wild ox himself.

In Sumerian, ušumgal refers to the great dragon, the ruler of all things.[42]

It’s important to specify these things in connection with the (great) dragon, as it indicates that he is also likely to be represented by the auroch, bison, wild bull, bovid in addition to the fact that they designate divinized primordial man.

We thus understand that through the adoration of the second, it is also the adoration of the first that is celebrated.

Report

We thus understand that ada-am has basically the same meaning as ku-uš(u): The wild bull father.

Kush = Kish

It’s worth pointing out here that kuš [ku-uš(u)] has the same meaning as kiš, since “uš” carries the idea of totality (we’ll see why in Part II) and kiš or keš means totality[43] .

Here again, this is in line with the symbolism of the star, since in proto-cuneiform the ideogram for kiš / keš is a star [with “scalariforms”]: .

Its ideographic meaning is that because it indicates the 4 cardinal points, it represents the completeness of the world, hence totality. As the lexicon rightly indicates, this is the name chosen for the first city of Sumer, which gave rise to the first Sumerian dynasty and, as we shall see, played the leading political and religious role in the most archaic Sumerian times.

We’ll come back to this a little later and see what can be said about this first dynasty of the city of Kish in detail in the appendices to Book II.

We’re just beginning to understand that the name City was chosen not only because it expresses the notion of totality, i.e. domination over the whole world, but also, and above all, because it associates this original city in a bond of spiritual filiation with the great divinity kuš(u), the primordial man divinized under the bull.

Note for believers concerning kush

By saying this, that Kush is one of the variants of the name of the great original god, I obviously don’t mean to imply that Kush (or Cush) the son of Ham, Noah’s great-grandson, is the one who was directly worshipped in the prehistoric caves, and that these were painted after his birth. The frescoes were obviously earlier, dating back to antediluvian times. Clearly, this name of the great divinity must have been known to Noah and his sons, Shem, Ham and Japheth, and the fact that Ham chose to name one of his sons by this name, would tend to prove that Ham at some point in his life tipped “over to the dark side of the force” to use a modern expression. Unless, of course, Kush was renamed or renamed himself in this way when he chose to position himself as the first post-diluvian king-grand-priest to restore the prehistoric pre-diluvian faith. We’ll have a chance to prove this in subsequent books, and in part in the appendices to the next book.

gu-uš

As for gu-uš, it means the ox gu the primordial man uš

Indeed, “gu” through “ gu4” designates a domestic ox[44] and “uš”, as we shall see in the next book, designates the primordial progenitor man at the foundation of the world, total man.

Of course, as we’ve already seen, not only. Remember that “g” and “k” are often interchangeable consonants in Sumerian.

Numerous examples are cited in the introduction to the Sumerian word index.

As a result, “gu” designates not only a domestic ox “ gu4“, but also, through its equivalence with “ku“, “a biological procreative ancestor”.

Su in hieroglyphic

If we turn to hieroglyphics, the hieroglyphic counterpart of šu: Sw designates the god Shou the son of Atoum, one of the primordial gods of Egypt, and also Sw

[45] the sun, also having the meaning of Sw

to ascend, to rise, in other words a divine being raised, put on high.

So we have confirmation that primordial man was, through some of his multiple avatars, divine, and the Egyptian god Shou is obviously one of them, worshipped under the symbol of the sun, the star.

Conclusion on šu

As we can easily understand, the mythologies of Sumer and Egypt borrowed their mythology and representation from a sacred culture older than their own, which had preceded them.

One of his many examples is this primordial father, whose name is adam(a), who was represented by a bison (ama, am) with the sign a/ad/ada equivalent of kuš (kush), guš (gush), represented by a bison/wild bull with the sign

šu, the latter more particularly indicating his status as the founder of humanity, his total domination.

Tak in Sumerian

It has been said that the proto-Cuneiform sign transliterates as šu or also tak.

We have seen the meaning of šu.

Let’s now look at the meaning of tak.

Literally, tak is a logogram which, along with its equivalent homophones taka, taga, tag, tà, designate a multitude of everyday actions that it would take too long to list them all (for example: weave, decorate, decorate; strike; fish, hunt, start a fire…)[46] .

This is logical, because, as we’ve seen, its associated sign designates, among other things, the hand, so tak carries all actions related to making, placing, fabricating and acting using the hands.

If we go beyond appearances and look at its symbolic meaning, it is then useful to break it down into ta-aka or te-aka[47] (note in the previous note that the Halloran lexicon breaks it down into te-aka)

Ta-aka:

Ta signifies a nature or character[48] (see for example Tán [proto-cuneiform men] defined as the contraction of [ta “nature, character” and an “sky” ].[49]

Thus, “ta” refers to a character.

We have seen on several occasions that “aka” designates a biological progenitor / progenitor ancestor.

So taka takes on the meaning of a biological ancestor-generator-procreator character, who makes, acts and creates with his hands.

Te-aka:

I can’t dwell here on all the meanings of “te”, whose polysemy and symbolic charge are very important. We’ll have ample opportunity to analyze them in subsequent books.

For our purposes here, te refers to a vulture which, as we’ll see in subsequent books, is a symbol of both the father of the gods and the mother goddess.

Just consider that the vulture hieroglyph transliterates as “A” [50][51] .

À which, as we’ve seen, is Sumerian for “father” a or a-a.

Conclusion on the meaning of the bison, plus the sign of the two horns plus the sign of the hand

It follows from what we have just seen that this rock figure of the bison with its two prominent horns and the hand sign can be read:

- a(da) – am ta/te-aka

a(da) – Ku-uš ta/te-aka

- a(da)- Gu-uš ta/te-aka

- Either the father a(da) / biological procreative progenitor ancestor Ku / the father-bull at the foundation of the world, with total domination uš / the character ta father/vulture te procreative progenitor

- Either the father a(da) / the ox gu / the father-bull at the foundation of the world, with total domination uš / the character ta père/vulture te procreative progenitor

- Either the father a(da) / wild bull am / the character ta father/vulture te ancestor progenitor biological procreator

The pettiforme Sanga

Evidenciation

We will now turn our attention to the pettiform below the bison figure:

It corresponds to the proto-cuneiform sanga, of which we have many similar variations.

This is sign 19 in the large comparative table in the appendix of this book:

Here, enlarged, are its many variations[52] :

It is equivalent to the other proto-cuneiform sign sanga with its various ideographic variations[53] :

Meaning

This pettiforme is extremely rich in meaning when placed in the eminently sacred context of the cave in general and this rock figure in particular.

Indeed, the proto-Cuneiform sanga gave rise in Sumerian to the words sañña2,3,4 or sanña2,3,4, both of which designate a sprinkler, used for ritual cleansing (it is also noted that this may refer to the director of a temple or an occupation such as that of a blacksmith) [54] .

In the context of this figure, where the ideogram sanga is oriented towards the bison above it, it’s obvious that this is above all a ritual purification operation for the latter, perfectly logical given that this is a wild bison-bull-symbol of the primordial man-father of the gods in the context of his temple-sanctuary that is the cave.

In any case, this symbol is as simple as it is powerful, and speaks for itself when it comes to demonstrating how closely the signs observed are associated with proto-cuneiform.

Inverted “T” signs

Evidenciation

There are many on the flank

Meaning

To understand the meaning of these signs, it is necessary to turn to demotic.

The demotic “i” is transliterated with the sign .

Interjection Ô

Note then that it means the interjection “Ô”. [55]

As in the expressions quoted below[56] :

For the first, “Ô Anubis”; for the second, “Ô Osiris” (wsir is the transliteration of the Egyptian name for Osiris[57] ); for the third, “Ô Hapy Osiris” (Hp is the transliteration of the Egyptian name for the bull god Apis, incarnation of the god Osiris[58] ); for the last, “Ô Tefnut”…

Add the fact that the bull is the incarnation of the KA of the god’s soul and that kA or skA designates a bull, whereas we have seen that a-ka = ugu, an ancestor in Sumerian.

Heil! Salute, acclaim, be praised

“i” is also a variation of iw :

Now, iw has the meaning of “to hail, hail, hail” or “may it be praised”:

This ties in with what we saw earlier (cf. sign III / Demotic contribution) that the Y, pronounced “a redoubled i“, is written in demotic, that it means “me, I”, that it introduces a magical name of divinity and that in the form pronounced yA, Ay or hy it means “to praise” or “to hail”.

Report

So the demotic “i” is strictly the same as Ô Osiris, Ô Apis, Avé César[61] or Heil Hitler.

It conveys the meaning of a greeting addressed to a god, an emperor, with the aim of acclaiming, praising and praying to him, in an act of devotion and veneration.

The shape of the “i” demotic

But how do you write the demotic “i”?

or

…

For example, here’s how to spell iAw “to be old”: [62]

The first letter from the right (Demotic is read from right to left like Arabic) is “i“.

or ii “eye” the first two from the right, etc.

Conclusion on the meaning of the “inverted T”

As you can see, these multiple inverted T-signs were so many “Ô” and “Heil” interjections, inviting devotees passing in front of the fresco to religiously salute this primordial father deified as father of the gods, represented in his animal twin form of the wild bison-bull, to acclaim, praise and pray to him, in an act of fervent, effervescent devotion and veneration.

Hieroglyph

We might add that this demotic greeting interjection is very logically an equivalent of the hieroglyphic hy which means “a greeting” and “a shout”[63] and also has the meaning of “to cheer” when redoubled hyhy

[64]

The fact that hy designates a cry cannot but make us think of ada, ad the father, which also means a cry in Sumerian[65] .

It is then particularly interesting to note that in hieroglyphic, there is a strict equivalence between hy and hi

to designate a husband, a spouse[66] .

So this greeting to the great deity is also a way of addressing him as father and husband. We’ll see in the next book that this is far from trivial, for this title of husband will also be a recognized title of the father of the gods as husband or spouse of the mother goddess!

Speckled buffalo

Evidenciation

Now let’s take a look at the speckled bison on the right of the fresco.

Meaning

What does it represent or mean?

Clearly, the fact that this bison is present on the fresco depicting the much more massive bison we have already identified means that they are both associated.

In fact, if you look closely at the shape taken by this speckled bison, you’ll see that it represents a skull – in other words, a man, a dead man, a deceased ancestor.

As we saw in the integration process section, point clouds can be used to represent figures. Here, it’s a bison, but it’s also a skull.

So let’s take a look at what the skull means and the fact that this bison-skull is speckled:

The skull

I’m not going to go into the symbolism of the skull here, as it’s multifaceted, but one of its major meanings is conveyed by its etymology.

Indeed, “skull” is “ugu” in Sumerian, with u.gù as the proto-Cuneiform ideogram[67] .

You’ll be familiar with this term by now, since ugu designates the biological procreative ancestor, the primordial father (cf. paragraph À = aka = ugu the procreator-generator).

If the literal meaning of u.gù is given as what is “after” “ù” the neck “gú”, we understand that by the play of its homophony, it also symbolically designates the ancestor to whom this head belongs.

Since etymologically, the skull is an ancestor, this is why the skull will always be found in ancestor worship. Although, to be honest, we didn’t really need Sumerian etymology to understand this. That said, the fact that it corresponds perfectly to a cult practice is yet further proof of its accuracy and its most archaic origins.

We can even add that u-gu means an ox by gu and, by u5, a ruler, someone at the top, a driver, a pilot as well as totality (symbolically a total ruler or of the totality of the world)[68] . We thus find the same imagery of the ox-man as in adam, kuš, guš already seen.

Basically, then, we understand that bison and skull here form a veritable play on words, since skull is a homophone of ox, and both are homophones of the primordial ancestor.

It should also be added in connection with this skull that, since it is here alone, dissociated from the head, it expresses the fact that this ancestor had his head cut off. Later in the books, we’ll see why the primordial ancestor (and indeed the mother goddess) was often depicted as headless.

Let’s take a look at why it’s been drawn here with speckles, a cloud of dots.

Speckles

To understand the meaning of speckles, let’s first look at the general meaning of decorating with different kinds of techniques, including speckles.

We will then focus on the apparent reason for this use.

The meaning of decorations in general

It’s enlightening to examine the general, generic Sumerian meaning of lines, speckles (clouds of dots) and color decorations.

Indeed, the Sumerian term “ugun” (with the ideograms u.dar or gùn) means “speckles, lines, inlaid ornamentation with coloured decorative elements on a surface”[69] .

The action of decorating (gùnu, gùn) is then described as being able to take on different forms: spotted, striped, streaked, speckled, spangled or starry, variegated, multicolored… [70]

It is interesting to note that this decoration has a sacred character.

Indeed, the term gi-gun4 (- na) or gi-gù-na designates a sacred building, with “guna” substituted for the meaning of “decorated”[71] . The logogram “gun(a)” therefore has the meaning of sacred.

On the other hand, the homonym of ugun, úgun, designates someone who has been anointed, on whom an anointing has been applied and who is a ruler (or a lady, a mistress, a leader).[72]

Now, “ugun” is nothing less than a contraction of “ugu” and “n”, meaning “ugu” “the procreative ancestor”[73] “n” “elevated”, i.e. divinized.

If “n” in Sumerian designates a “discrete point”, it is a letter that marks divinization, as it designates elevation, signifying the fact of “being elevated” [74]

Thus, the double meaning of ugun is the elevated (or divinized) procreative progenitor.

NB: Remember that the use of the word “elevated” in the passive sense implies that this god was not elevated before he was elevated. Indeed, the true God doesn’t need to be elevated by humans, since he has always been on high. On the other hand, the fact that a being needs to be elevated to become a god implies that he wasn’t a god before he was elevated, that he was merely a father-ancestor who was deified either during his lifetime or after his death.

With “ugun”, we’re talking primarily about an etymological avatar of the primordial father of mankind.

Conclusion on the meaning of decorations

What does all this mean for our understanding of cave decoration, including speckles?

That they have a sacred, eminently cultic character; they are therefore carried out in normal times in a place of worship, a temple, a sanctuary. Their presence is therefore, if proof were still needed (??), a further line of evidence to demonstrate that the cavern is a temple-sanctuary.

They are used to highlight the gods, their anointing, i.e. their designation as dominant entities, and also their elevation, their divinization.

First and foremost, ugun decoration is used to represent the primordial man, the first biological procreative ancestor ugu as an anointed one, a ruler, elevated n to the rank of god in his dedicated temple.

The specific meaning of speckles

First of all, it’s interesting to note that the notion of anointing is particularly well conveyed by speckles, since dots can – and, as we’ll see, easily do – conceptually represent drops, whether of water or another liquid.

There is, however, another aspect that the point speckle or point cloud represents.

Zatu sign of the speck

One of the meanings of the speckle or cloud of dots is to convey the notion of death, of the decomposition of the object or being represented or signified by the ideogram, as if to indicate that it has returned to dust, turned to dust, decomposed.

Indeed, among the many zatu signs of the proto-cuneiform, we find the cloud of points :

zatu

general meaning of the zatu sign

We’ve already mentioned that the zatu sign is a very important and recurring sign in proto-cuneiform, and I’ve mentioned that it’s a sign of death, but also of rebirth.

Let’s find out why.

Explanation (taking all the meanings of zatu from the Halloran lexicon):

The first meaning of zatu is that it designates death or killing.

There is in fact a zatu sign for uš in its sense of death, to die, to kill[76] , for til in its sense of to complete, to finish, to cease, to perish [77] for the proto-cuneiform bad which refers to the Sumerian suñin, sumun, sun, šum4 which have the meaning of decomposition, something rotten, the past, to ruin, old, ancient[78]

As an indication and to be perfectly exhaustive on the occurrences of the meanings of zatu in the Halloran lexicon it is also associated with :

- To a brother in religion whose proto-Cuneiform ideogram uri3 refers to the Sumerian šeš[79] , a brother in religion who visibly assumes, among other things, the traits of an eagle, as the proto-Cuneiform ideogram šeš mirrors the Sumerian urin, ùri which designate an eagle (and the blood[80] which can be synonymous with death by uš). One of the meanings of šeš is to weep, to mourn, to lament, to wail.[81]

In the following books, we’ll see who this eagle is and why it’s so synonymous with death.

This brother in religion is also an Akkadian (we’ll see who this brother in religion is, this Akkadian, a little later in the analysis of the Chinese horse of Lascaux).

- To a dwelling (by maš-gána[82] ) obviously linked to a cult (worship platform) and/or a king (by barag, bára, bár; bara5,6[83] ), an inner sanctum (by agrun[84] ).

Moreover, maš-gána means the field, the crop (gána)[85] [86] of the star (maš; reminder: the ideogram of the star is called maš in proto-cuneiform; cf. explanation Meaning of the cross)

In other words, the place where a star , a divinity or a sanctuary is conceived is a place of death.

- To an auroch, bison, wild bull by alim because alim has the particularity of also being a zatu sign[87] and to a team of donkeys or animals (by the proto-cuneiform ideogram erim which refers to the sumerian bir ).[88]

So when you see an auroch, a bison, a wild bull or a team of donkeys or other animals, as is very often the case in cave frescoes, you have to understand that the idea is one of death, of a herd heading towards death, whose ultimate purpose, as we saw above, is for the humans they represent to end up becoming stars, deities.

NB: For your information, the proto-cuneiform ideogram corresponding to bir is sign 10 in the comparative table in appendix , which corresponds to the sign

identified by Sauvet & Wlodarczyk.

When you see this sign, know that this is what it means.

Explanation by breaking down za-tu :

We’ve said that zatu is a sign of death, but, as always in the thinking of the original false universal religion, this death is a prelude to rebirth.

This is what the word zatu itself conveys if you break it down.

Indeed, za-tu very synthetically means that which makes, causes to be reborn, is reborn, is transformed into tu/du[89] the precious stone za[90] .

We’ll look in detail at the symbolism of the stone, which is polysemous, but it’s important to understand that the gemstone represents, as I said in the introduction, the individual’s success in achieving sublimation.

From a clay stone full of imperfections, filled with slag and blemishes while alive, to the dust and decay he (re)became through his death and return to “the underworld, the realm of the dead, of dust and rock”, he is said to be able to transform himself, after undergoing a cycle of regeneration, into a precious stone, the equivalent symbol of the star, symbolizing his purification, his transformation and his attainment of divinity. This is “the true Grail, the philosopher’s stone of the alchemists, the true quest underlying these symbols, the immortality acquired through the sublimation of the being who undertakes the inner quest in order to leave behind his sinful human nature, rid himself of his dross, become of divine essence and thus re-merge with the great original All”.

Thus, zatu is a sign of death, but with a view to a promised rebirth under a purified, divine being.

The skull also expresses the idea of rebirth

I should add that the skull also expresses the idea of rebirth, but this is not necessarily highlighted in the fresco analyzed.

I’ll come back to why the skull represents rebirth later, particularly in the more in-depth examination of the cavern in volume 6.

The branches

We’ll now look at the direction of the branches next to the speckled buffalo.

Evidenciation

Meaning

To understand what these branches mean, we need to turn to sumerian etymology.

The proto-Cuneiform ideogram of the branch refers to the logogram še.

The branch or ear of wheat in Sumerian

In Sumerian, še literally refers to grain, barley, wheat or corn[91] .

But through its various double meanings, it also represents the father as a man tied up, a captive (by še29[92] ) literally someone bound with a rope “éše” [93] equivalent of lú-éše, i.e. a fettered or bound human who has died and turned into dung, excrement (by še8 (ou šéš, še10))[94] .

Why can we say it’s the father?

Just note that še by šè is a portion, a part[95] and by še7 the pouring rain[96] .

Now, these are two synonyms of the word father that we have already seen:

- The portion in the analysis of the hand sign šu means, among other things, a share, a portion, and can be associated with maš the star, which also means a twin – someone who leaves, goes out with a portion.

- La pluie (à verse) par le fait que “a” signifie père et aussi un déluge[97] .

Moreover, še is synonymous with eš [eššu is an ear of corn[98] ] which more specifically designates by “éše” or “eš“, the one tied up by the rope (again, we’ll see by whom and why this symbolism) and also the anointed one[99] “éše” i.e. the king, the lord, dead, “eš” is also a tomb; all meanings linked to the situation of the primordial father.

The ear of wheat in Egyptian

If you doubt that the branch, the ear of wheat, refers to the father, let me remind you of its meaning in Egyptian: it: father, barley, cereal…[100]

Conclusion on the meaning of these ears of wheat

At this point in the fresco, these lying branches / ears of wheat, lying to mark that the father to whom they refer is dead, in perfect analogy with the speckled bison, which also expresses the idea that the primordial father decomposed after his death and became dust, also serve to signify that he decomposed and turned into dung, excrement.

The horse and the branch: anshe

Let’s take a look at another branch, the one associated with the horse and its signifier.

Evidenciation

Meaning

It’s extraordinarily simple, profound and demonstrates the wisdom of using proto-cuneiform to decipher cave paintings.

What is the Sumerian word for an equine (donkey, primrose, horse)?

Anše!!![101]

Tell me what the mathematical probability is that this animal is called anše and that the branch in its prolongation is called še, as if to mark the decomposition of this word into an-še?

It is certainly very low.

But what does anše really mean (symbolically) in a religious context?

To find out, just break down the word into an-še.

According to the Halloran lexicon, an means heaven, paradise, the father of the gods An; “…” and in its verbal form, it means to be above “…”.

Since “a” and “ e4 ” are equivalent, “an” is a homophone of “en”, meaning a dignitary, a lord, a high priest, an ancestor, a statue…

As we have already seen, “n” in Sumerian is a letter that means “to be elevated”.[102]

As for “a”, we’ve seen that this letter refers to the father.

So “an” literally means the father raised. This is the very meaning of the name of the father of the Sumerian gods, An or Anou.

This meaning is exactly the same as that of the god El (or al or even la), which is a contraction of “a” or “ e4” [103] and “íla, íli, íl” “to be elevated”[104] .

It is easy to understand why An, or Anou, is the father of the Sumerian gods:

It is, literally, an ancestor father elevated to the rank of the gods, to heaven.

Take a look at what the Larousse says about the title of the god An in Assyro-Babylonian mythology: “Anou, whose very name means “heaven”, therefore reigns over the celestial spaces. “…” He is the god par excellence, the supreme god. All the other deities honor him as their father, i.e., as their leader.” (F.GUIRAND, 1996, p. 74)

As we’ve already seen with the term ugun, this etymology allows us to understand that An(ou) is not a father of the gods, as if he had always been a god, but that he is a human father, a high priest, an ancestor, a lord, a dignitary who became a god, after being elevated, during his lifetime or after his death.

Indeed, elevation implies that there was previously an inferior or lowered state. A real god doesn’t need to be elevated, since by nature he’s already “on top”.

If we return to anše, according to the Halloran lexicon, še can have the ending meaning “to go as far as…”.

In other words, anše means word for word “the father raised up to… heaven“, since “an” also refers to heaven.

Now do you understand why the donkey is a symbol, another animal avatar of the father of the gods?

Do you also understand the archaic origin of our word donkey?

As for this specific point, even Wikipedia mentions it! :

“The oldest attested form of the pre-Indo-European name for donkey in the Mediterranean and Near Eastern regions is thought to be sumerian anšu, by which Émile Benveniste explains ὄνος (ónos), the ancient Greek to which Latin asinus is related. Old French asne is attested in the 10th century: according to the “Trésor de la langue française informatisé”, its first occurrence is in the Passion du Christ dite de Clermont. The spelling “ane” is attested in the 13th century. The word has been used to designate the domestic donkey since the 10th century. Because of its origin, the donkey has no Indo-European name. Rather, it is a Near Eastern heritage that spread into European languages from Latin. Thus the Latin asinus, derived from the Sumerian anshu, has passed into all languages except Romanian.

Wikipedia – donkey

So, if Wikipedia says so… (smile)

To be honest, we wouldn’t have needed Wikipedia to understand this, since the correlation is obvious, but it’s interesting to see that the influence of Sumerian, which we might a priori believe to be a language far too old and far too different to ever have had any influence on our culture, is in fact very strong.

So, with the name of our nice, stubborn French donkey, we’re unknowingly naming the Sumerian word for this animal nearly 4,500 years later, which is another animal avatar of the primordial man deified under the father of the gods and of which An was one of the names.

Anše = kiš

Another very important point to highlight in relation to the term anše is that it is equivalent to the logogram kiš.

We’ve already talked about it

We’ll come back to this in a little more detail later on.

But this is an extremely important point.

You may have the impression that this term kiš is very common in Sumerian, as this book will be talking about it a lot, but in fact its occurrences are very rare.

It is found as a root in only 4 words: kiš, kiša, kiši, kišib, kišik ;

and the only two times it is designated as an ideogram in Sumerian logograms is for its literal meaning of the city of Kish, which designates the entire politico-religious world of Sumer[105] and for the name of the donkey anše[106] and another animal avatar we’ll see later.

So there’s a very singular, extremely specific, unique bond between the father of the gods and Kish. We’ll take a closer look at why this is, and what it implies.

The Ô and Re signs on the horse

But perhaps you doubt that this donkey-horse is also the great divinity?

I invite you to read with me what you see drawn on its side:

By now you should be able to decipher it easily: Ô / Heil Re!

So the whole equid fig with the branch plus the sign of Re and the interjection “i” is read as a whole: i re anše (or aneš) ! or Ô / Heil Re anše (or aneš)!

Incidentally, this other avatar name of the father of the gods, Anesh, is what gave rise to the name of the Oannes gods, the Innus name given to the god Pan[108] , and later the name of the Roman Janus.

Note that Anesh is a double god because he includes the logogram eš “part, portion” which makes him a twin, and the same applies to the Roman father of gods, Janus, who is the Roman double god par excellence.

But as the books progress, we’ll see in greater detail the archaic origins of the etymology of all the divinities, notably with the explanatory index of the proper names of divinities in volume 4.

The branch and the backbone

I also invite you to notice that the branch associated with the equid/donkey is positioned in such a way that it seems to (re)form its backbone.

I draw your attention to this point, because we’ll see in the following books that just as the great divinity was depicted as headless, she will also be fairly regularly portrayed in mythology as having had her spine broken. We’ll see why.

The fact that his column is reconstituted here serves to signify his rebirth.

This is also why the branch associated with the equine does not have the same significance as the lower branches, which, as we have seen, signify the decomposition of the primordial father upon his death.

The tectiforme and the horse

I’d also like to draw your attention to the tectiforme , which lies just below the equidae and links them together.

I won’t go into the meanings of tectiforms here.

Let’s just keep in mind for now that they can represent the father of the gods as well as the mother goddess, their body and a temple, a sanctuary.

Conclusion on the large Marsoulas panel

Once these various elements have been deciphered using proto-cuneiform and other ideographic reference languages, this major fresco in the Marsoulas cave becomes clearer.

If we put the fresco back in its reading direction, we have to start at the bottom right with the primordial ancestor under the speckled buffalo-skull (ugu) who decomposes in death (zatu), then to his left with the symbols of the elongated branches which describe him as having become dung (še8), but who, passing through the sanctuary (the tectiforme) that is the cave, finally emerges purified (the sanga signs on the left), regenerated as the father of the gods, as well as in the form of the great divine bison adam, kush, gush (top left) and the donkey (anše / aneš / kiš) (top right), in both cases a symbol of the supreme god who is the object of all the devotion and adoration (i re) of his devotees.

FOOTNOTES AND REFERENCES

[1] (CNIL, 1996?, p. 1)

[2] The A is the letter Champollion deciphered when he decoded a queen’s cartouche inscribed on an obelisk in the Temple of Isis in Philae; it contained a Greek text mentioning the name Cleopatra. He already knew the hieroglyphic phonetic counterparts of the P, T, O and L in this word. When he saw that a hieroglyph, in this case the … vulture, appeared twice, he logically deduced that the vulture was the hieroglyphic counterpart of the …A, “Cleopatra” containing two A’s. This is how he deciphered her name. This helped him gradually decipher everything else. It was one of the first stones in his extraordinary edifice of deconstruction, deciphering and revelation of a hidden, mysterious language that was thousands of years old.

[3] a, e4 = noun. : water; watercourse, canal; seminal fluid; offspring; father; tears; flood (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 3) with translation in Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: a, e4 = nominative = water, watercourse, canal, seminal fluid, offspring, father, tears, flood.

[4] a5= (cf., aka). (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 3)

[5] aka, ak, ag, a5 = to do, act; to place; to make into (something) (with -si-) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 18) with translation in Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: aka, ak, ag, a5 = to do, act; to place; to make into (something) (with -si-)

[6] a-ka = (cf., úgu) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 72)

[7] a-ugu4 [KU] = the father who begot one (‘semen’ + ‘to procreate’). (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 74) with translation in Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon = a-ugu4 (KU) = the father who begot one (‘semen’ + ‘to procreate’).

[8] a-a = father (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 71). Translation in Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: a-a = father.

[9] The two oblique or vertical lines; Sources: https://www.hierogl.ch/hiero/Signe:Z4 ; Gardiner p. 536, Z4 . See also Gardiner p. 59, §73,4

Two oblique lines, less often vertical

:

In some cases replaces human representations considered magically dangerous, e.g. Axt(i)

the two glorious ones in place of

[10] Cf Volume 4 / Lexique hiéroglyphes-français: Axt Akhet (the goddess); arable land; serpent uræus; eye (of a god) see irt eye (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 31) ; flame ; horizon, king’s tomb / (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 5)

[11] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French Lexicon: Axty inhabitant of the horizon; residing on the horizon (idiom.), an epithet of god / (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 5)

[12] Sources: https://www.hierogl.ch/hiero/Signe:Z4 ; Gardiner p. 536, Z4 . See also Gardiner p. 59, §73,4: In M.E. is always the phon. “y” (Pronunciation: [j], the i in yacht, the i in ami) due to its constant previous association with words of dual form, i.e. ending in i (y), e.g.

.

y is always the final consonant; it has a specific use and is rarely interchangeable with it.

[13] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon: rwty or

Routy (the double lion god, the twins Shou (Sw) and Tefnout (tfnt)) lion’s den outside, exterior (n.) intruder, foreigner (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 183)

[14] Source : https://www.hierogl.ch/hiero/Signe:Z4A : Same as

but less frequent

We find it in: pAwty primordial god; old-family man; primordial; with variation pAtyw or pAty

or paty

primordial god; pAti

old-family man (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 108) ; cCf. pAwt primitive times.

[15] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon: pAwt pAt

primitive times pAwt

burden, weight (of illness) (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 108)

[16] Proto-Elamite Sign Frequencies / Jacob L. Dahl / University of California, Los Angeles / https://cdli.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/articles/cdlb/2002-1.pdf

[17] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wikiélamite_linéaire#/media/Fichier:Linear_Elamite_alpha-syllabary.jpg

[18] zu, sú : n., wisdom, knowledge. v., to know; to understand; to inform, teach (in marû reduplicated form); to learn from someone (with -da-); to recognize someone (with -da-); to be experienced, qualified.

adj., your (as suffix). pron., yours (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 17) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: zu, sú = wisdom, knowledge. Verbs: to know, to understand; to inform, to teach; to learn from someone (with -da); to recognize someone (with -da); to be experienced, qualified. Pronoun: your, yours.

[19] zú, su11[KA] : tooth, teeth; prong; thorn; blade; ivory; flint, chert; obsidian; natural glass. (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 17) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: zu, sú = zú, su11[KA] tooth, teeth; prong; thorn; blade; ivory; flint; obsidian; natural glass.

[20] a, e4 = noun. : water; watercourse, canal; seminal fluid; offspring; father; tears; flood (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 3) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: a, e4 = nominative = water, watercourse, canal, seminal fluid, offspring, father, tears, flood.

[21] https://www.hethport.uni-wuerzburg.de/luwglyph/ –) sign list / p.10

[22] ída, íd, , i7 : river; main canal; watercourse (ed,’to issue’, + a,’water’) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 18) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: i7= (cf., ída) -) ída, íd, , i7 : river, main canal, watercourse (ed ” generate + a “water”).

[23] ia2,7,9 í: five ; ìa, ì: n., oil, fat, cream ; ia4, i4: pebble, counter. (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 11) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: ì = (cf., ìa) -) ia2,7,9 í = five ; ìa, ì = nouns: oil, fat, cream ; ia4, i4: pebble, counter

[24] For a complete analysis of the hand symbol, see Volume 3 / The symbol bible / The hand symbol

[25] šu : n., hand; share, portion, bundle; strength; control ; v., to pour. (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 16) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: šu = nouns: hand, share, portion, bundle; strength, control/Verbs: pour

[26] šuš2,3 : to rub, anoint (with oil) (su, ‘body’, + eš, ‘to anoint’). (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 48) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: šuš2,3= to rub, anoint (with oil) (su, ‘body’ + eš, ‘to anoint’).

[27] Via Latin Christus, from Ancient Greek Χριστός, Khristós, from χριστός, khristós (“anointed”). The word is derived from the Greek verb χρίω (chrī́ō), meaning “to anoint”. In the Greek Septuagint, christos was used to translate the Hebrew מָשִׁיחַ (Mašíaḥ, “messiah”), meaning “[the one who is] anointed”. https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christ

[28] šuš4: to fell trees; to chop away (reduplicated šu, ‘hand’). (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 48) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: šuš4 = to fell trees; to chop away (reduplicated šu, ‘hand’)

šu2,4, šuš2: to overthrow; to throw down; to go down; to set, become dark, be overcast (said of the sun); to cover (with -da-) (reduplicated šu, ‘hand’; cf., šub). (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 48) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: šu2,4, šuš2, = to overturn, to bring down, to fall, to make dark, to become dark, to become overcast (said of the sun); to cover (with -da-) (reduplicated šu, ‘hand’; cf., šub) ;

[29] Šu12 = (cf., šùde) —) šùde, šùdu, šùd, šu12: n., prayer, blessing ; v., to pray, bless (šu, ‘hand’, + dé, ‘to hail’) (A.Halloran, 1999, pp. 16, 24) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: Šu12 = (cf., šùde) —) šùde, šùdu, šùd, šu12 = nouns: prayer, blessing; verbs: to pray, bless (šu, ‘hand’, + dé, ‘interpeller saluer, héler, acclamer’).

[30] Šú = (cf., šúš) –) suš : to sit down; to reside (su, ‘body, relatives’, + uš8, ‘foundation place, base’; cf., tuš) (A.Halloran, 1999, pp. 16, 48) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: Šú = (cf., šúš) –) suš = to sit down, to reside (su, ‘body, relatives’ + uš8, ‘foundation place, base’; cf., tuš).

[31] ñiš 2,3 ñeš2,3, uš: penis ; man (self + to go out + many; cf., nitaĥ2and šir) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 46) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: ñiš 2,3 ñeš2,3, uš: penis, man (self + to go out + many; cf., nitaĥ2 and šir)

[32] šu: n., hand; share, portion, bundle; strength; control ; v., to pour. (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 16) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: šu = nouns: hand, share, portion, bundle; strength, control/Verbs: pour

[33] maš : one-half; twin (ma4, ‘to leave, depart, go out’, + šè, ‘portion’) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 47) ; Cf Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: maš = moitié, jumeau (ma4, ‘to leave, depart, go out’ + ‘šè’ ‘part, portion’)

[34] kušu : (cf., kušumx) = kušumx, kušu [u.piriñ] = herd of cattle or sheep (A.Halloran, 1999, pp. 47, 61) ; Cf Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: kušu = (cf., kušumx) = kušumx, kušu [u.piriñ] = herd of cattle or sheep

[35] sún : aurochs cow, wild cow; beerwort (su, ‘to fill, be sufficient’,+ un, ‘people’) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 38) ; Cf Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: sún = aurochs cow, wild cow; beerwort (su “to fill, be sufficient” + un, “people”.

[36] sun4, sum4, sùl, su6 = chin; lower lip; beard (cf., si, ‘long, thin things’, and tùn, ‘lip’) ; (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 38) ; Cf Volume 4 / Lexique sumérien-français : sun4, sum4, sùl, su6 = chin, lower lip, beard (see “si” “long, thin thing” and “tùn” “lip”)

[37]Šún [MUL]: n.,star. v., to shine brightly. (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 38) ; Cf Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon : šún [MUL] = a star; to shine, to sparkle brilliantly

[38] Kušum : to scorn, reject, hurt; to abandon (ki, ‘place’, + ušum, ‘solitary’) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 61) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: Kušum = to scorn, reject, hurt; to abandon (ki “place” + ušum, “solitary”).

[39] Ki : n., earth; place; area; location; ground; grain (‘base’ + ‘to rise, sprout’) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 12) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: Ki = nominative: earth; place; area; location; ground; grain (‘base’ + ‘to rise’ ‘to sprout’)

[40] ušum, ušu: n., dragon, composite creature (uš11, ‘snake venom’, + am, ‘wild ox’); adj., solitary, alone. (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 70) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: ušum, ušu = dragon, a dragon, literally a wild ox with snake venom (uš11, ‘snake venom’, + am, ‘wild ox’). Adjectives: solitary, alone.

[41]ù-sun [BAD]: wild cow, cf. sún (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 151) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: ù-sun (BAD) = wild cow, cf., sún.

[42] Ušumgal: lord of all, sovereign; solitary; monster of composite powers, dragon (ušum, ‘dragon’, + gal, ‘great’) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 70) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: Ušumgal = lord of all, sovereign; solitary; monster of composite powers, dragon (ušum, ‘dragon’ + gal, ‘great’)

[43] kiš, keš : totality, entire political world (name of the powerful city in the north of Sumer that first bound together and defended the cities of Sumer) (places + many) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 47) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: kiš, keš = totality, entirety of the political world (name of the powerful city in the north of Sumer that first bound together and defended the cities of Sumer) (place + many).

[44] gud, guð, gu4 = n., domestic ox, bull (regularly followed by rá ; cf., gur4 (voice/sound with repetitive processing – refers to the bellow of a bull) v., to dance, leap (cf., gu4-ud). (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 23)Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: gud, guðx, gu4 = domestic ox (regularly followed by rá; cf., gur4) (recurring sound referring to the mooing of the ox. Verbs: dance, jump (cf., gu4-ud).

[45] Sw to be empty; to lack; to be destitute, deprived, deprived of; to be in want of; lack, scarcity indigent, needy (n.) blank papyrus scroll Shou to ascend, to rise sun, sunlight dry, parched (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 321)

[46] taka, taga, tak, tag, tà : to touch, handle, hold; to weave; to decorate, adorn; to strike, hit, push; to start a fire; to fish, hunt, catch (can be reduplicated) (te, ‘to approach’ + aka, ‘to do, place, make’) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 30) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian/French Lexicon: taka, taga, tak, tag, tà = to touch, take, hold; to weave; to decorate, adorn; to strike, tap, push; to start a fire; to fish, hunt, catch (can be reduplicated) (te, ‘to approach’ + aka, ‘to do, place, make’.

[47] Note in the previous note that the Halloran lexicon breaks it down into te-aka)

[48] ta, dá : n., nature, character (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 16) Volume 4 / Sumerian/French lexicon: ta, dá = nature, character, character

[49] Tán [MEN] : to become clean, clear, light, free (ta, ‘nature, character’ + an, ‘sky, heaven’) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 38) Volume 4 / Sumerian/French Lexicon: Tán [MEN] = to become clean, clear, light, free (ta, ‘nature, character’ + an, ‘sky, heaven’).

[50] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon: A = Vautour / (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 1)

[51] Reminder: See Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon / transliteration: “A” = (vulture) = pronunciation: [ʔ], hamza (“coup de glotte”) as in Arabic.

[52] (Falkenstein, 1936, pp. 133, 135)

[53] (Falkenstein, 1936, p. 168)

[54] sañña2,3,4,sanña2,3,4 :a sprinkler, used for ritual cleaning ; economic director of a temple or occupation (such as all the smiths) (sañ, ‘head’, + ñar;ñá, ‘to store’) (SANGA) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 64) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian/French Lexicon: sañña 2,3,4, sanña2,3,4 = a sprinkler, used for ritual cleansing; economic manager of a temple or occupation such as a blacksmith (sañ, ‘head’ + ñar;ñá, ‘to store’) (SANGA)

[55] https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/publications/demotic-dictionary-oriental-institute-university-chicago / I, p.1

[56] https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/publications/demotic-dictionary-oriental-institute-university-chicago / I, p.3

[57] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon: wsir Osiris (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 84)

[58] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon: Hpw Taureau Apis Hp (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 207)

[59] https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/publications/demotic-dictionary-oriental-institute-university-chicago / I, p.3

[60]https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/publications/demotic-dictionary-oriental-institute-university-chicago / I, p.2

[61] As for the deeper etymological meaning of the word Caesar, the demotic is very useful for understanding it. It contains the following declensions: Gysrys, gysrws, gysrs, qysr, qysrw, qysrs, qsrAys, kysls, Ksrs, Gesrs, gysrys, g(y)srws, gysls, gsrA, gsrAs, gesrs, qysrs, which establishes that the origin of this name is gw-sar-as or gus-sar-as. We already know what g/ku and us mean… we’ll see what sar and as mean in the next book. We’ll understand how completely this name is in the spiritual filiation of the primordial divinized father.

[62]https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/publications/demotic-dictionary-oriental-institute-university-chicago / I, p.4

[63] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon: hy salut!, cry (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 194)

[64] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon: hyhy acclaim, make an acclamation (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 194)

[65] ada, ad : n., father; shout; song. v., to balk. (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 18) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon = ada, ad = nominative: father, shout, song / verb: to balk

[66] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon: h cour variant of hi mari, husband (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 193)

[67] ugu [U.GÙ] : n., skull; top of the head; top side; upper part; voice (cf., ùgun, ugu(4)) (ù,’after it’, +

gú,’neck’) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 18) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: ugu [U.GÙ] = nominative: skull, top of the head, upper face, upper part or side, voice (cf., ùgun, ugu4) (ù, “after him”, + gú, “neck”).

[68] u5 : n., male bird, cock; totality; earth pile or levee; raised area (sometimes written ù) ; v., to mount (in intercourse); to be on top of; to ride; to board (a boat); to steer, conduct.adj., (raised) high, especially land or ground (sometimes written ù) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 4) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: u5 = nominative: male bird, rooster, whole, heap of earth or dyke, elevated area. Verbs: to climb, to be at the top, to go up, to lead, to drive, to pilot/rendered high, especially for land and soil (sometimes written with ù)

[69] ugun [U.DAR/GÙN] = adorning speckles and lines; inlaid decoration (u, ‘ten, many’, + gùn, ‘to decorate with colors’ may be popular scribal etymology; cf., ug, ‘lion, any deadly cat’ + n, ‘discrete point’) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 69) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon = ugun[U.DAR/GÙN] = speckling and decorative lines; inlaid decoration (u, ‘ten, many’ + gùn, ‘decorate with colors’ may be popular scribal etymology; cf. ug, ‘lion, any deadly cat’ + ‘n, ‘discrete point’).

[70] gùnu, gùn = n., dot, spot (circle + discrete point; cf., ugun) v., to decorate with colors, lines, spots; to sparkle; to put on antimony paste makeup. adj., dappled; striped; speckled, spotted; spangled; variegated, multicolored; embellished, decorated; brilliant (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 37) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon = gùnu, gùn = dot (circle + discrete dot; see ugun); decorate with colors, lines, dots; glitter; put make-up paste on antimony; adjectives: spotted, striped, speckled, speckled, spangled or starred, variegated or multicolored, embellished, decorated, brilliant.

[71] gi-gun4 (-na), gi-gù-na: sacred building (‘reeds’ + ‘decorated temple’) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 92) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon = gi-gun4 (-na), gi-gù-na = sacred building (‘reeds’+’decorated temple’).

[72] úgunu, úgun[GAŠAN] = lady, mistress, ruler; ointment, application (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 69) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: úgunu, úgun[GAŠAN] = lady, mistress, ruler; unction, application.

[73] (cf paragraph aka = ugu the procreator-generator).

[74] Nun : n., prince, noble, master (ní, ‘fear; respect’,+ un, ‘people’ ?) v., to rise up (n, ‘to be high’,+ u5, ‘to mount; be on top of; raised high’). adj., great, noble, fine, deep (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 38) ; Volume 4 Sumerian-French Lexicon: Nun = nouns: prince, noble, master (ní, “fear, respect” + “a” “people” ?) / verbs: to be raised (nouns: “n” “to be raised” + u5, “to mount, to be on top of, made great”) / adjective: great, noble, fine, deep.

[75] (CNIL, 1996?, p. 242)

[76] úš: n., blood; blood vessel; death [? zatu-644]. v., to die; to kill; to block (singular hamtu stem). adj., dead (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 8) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: uš = nominative: blood, blood vessel, death/Verbs: to die, to kill; to block/adjective: death (zatu sign)

[77] til : to be ripe, complete; to pluck; to put an end to, finish; to cease, perish (iti, ‘moon’, + íl, ‘to be high; to shine’ ?) [? ZATU-644]. (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 8) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: til: to be mature, complete; pluck, gather; complete, finish; cease, perish (iti “moon” + íl “to be high; to shine” [? ZATU-644].

[78] suñin, sumun, sun, šum4[BAD] : n., rot, decay; something rotten; the past (su, ‘body’, + ñin, ‘to go’) [? ZATU-644]. v., to decay; to ruin. adj., old, ancient (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 65) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: Sun = suñin = sumun, sun, šum4 [BAD] = rot, decay, decomposition; something rotten; the past (su “body” + ñin, “to go”); to decay, ruin; old, ancient.

[79]šeš , šes : brother; brethren; colleague [uri3=ZATU-595] (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 48) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: šeš, šes = brother, spiritual brother (ang. Brethren); colleague.

[80] urin, ùri [ŠEŠ] = urin, ùri [ŠEŠ] : eagle; standard, emblem, banner; blood [ŠEŠ ZATU-523] (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 70) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: eagle, emblem, banner, blood

[81] šeš2,3,4 : to weep, cry; to mourn; to wail (reduplication class) (to become moist ?) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 48) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: šeš2,3,4 = to weep, to lament; to mourn by weeping; to wail (reduplication of “devenir humide”)

[82] maš-gána: settlement (Akk. loanword from maškanum, ‘location, site’, cf., šakaanum ‘to place’) (ZATU- 356) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 118) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: maš-gána: dwelling, (loanword from Akkadian maškanum, ‘location, site’ cf., šakaanum ‘to place’) (ZATU- 356)

[83] barag, bára, bár ; bara5,6 : throne dais; king, ruler; cult platform; stand, support; crate, box; sack; chamber, dwelling (container plus ra(g), ‘to pack’) [? BARA2 ; ZATU-764] (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 52) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: barag, bára, bár; bara5,6 = throne canopy, king, ruler, cult platform, support, crate, box, sack, chamber or reservoir or cavity, dwelling

[84] agrun: inner sanctuary [ZATU-413 archaic frequency: 4] (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 50) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: agrun: inner sanctuary [ZATU-413].

[85] gána, gán: tract of land, field parcel; (flat) surface, plane; measure of surface; shape, outline; cultivation (cf., iku) (cf., Orel & Stolbova #890, *gan- “field”) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 50) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: gána, gán = piece of land, field plot; flat surface; surface measurement; shape, outline; cultivation (cf., iku).

[86] It is the counterpart of the Semitic Hebrew gan for garden, paradise

[87] Alim = wild ram; bison; aurochs; powerful (Alim = zatu-219 [Gir3]) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 50) ;

Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: Alim = wild ram; bison; auroch; powerful (Alim = zatu-219 [Gir3])

[88] bìr [ERIM]: team (of donkeys/animals) (ba, ‘inanimate conjugation prefix’, + ir10, ‘to accompany, lead; tobear; to go; to drive along or away’, the plural hamtu for ‘to go’, cf., re7) [?? BIR3 ZATU-143 ERIM]. (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 50) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: Alim bìr [ERIM] = team (of donkeys, animals) (ba, inanimate prefix + ir10, “to accompany, lead; to carry; to go; to drive with or away, the plural hamtu for ‘to go’ cf. re7)

[89] tud, tu, dú : to bear, give birth to; to beget; to be born; to make, fashion, create; to be reborn, transformed, changed (to approach and meet + to go out). (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 24) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: Tud, tu, dú = to bear, to give birth to; to beget; to be born; to make, fashion, create; to be reborn, transformed, changed (to approach and meet + to go out).

[90] za2 = precious stone, gemstone; bead; hailstone; pit; kernel (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 24) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: za2 = precious stone, gemstone; bead; hailstone; pit; kernel.

[91] še : n., barley; grain; a small length measure, barleycorn (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 16) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: še = barley; grain a small length measure, wheat or maize. May indicate here, depending on the speaker’s point of view

[92] še29[LÚ×KÁR, LÚ-KÁR] = šaña = ĥeš4 [LÚ×KÁR, LÚ-KÁR] : captive (tied up with a rope éše; cf., lú-éše). (A.Halloran, 1999, pp. 16, 28) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: še29[LÚ×KÁR, LÚ-KÁR] = šaña = ĥeš4 [LÚ×KÁR, LÚ-KÁR] = captive (tied up with a rope éše; see lú-éše)

[93] éše, éš[ŠÈ]: rope; measuring tape/cord; length measure, rope (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 20) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon éše, éš[ŠÈ] = rope, measuring tape/cord; length measure, rope

In the symbolism of ropes, we’ll see that there are two terms for rope: “éše” and “um”. The latter, with its striking double meaning, symbolizes a lady/queen who is both nurturer and witch, figuratively tying up her children and prey (including her lovers) with ropes.

[94] še8 = voir šéš, še10 excrement, dung (A.Halloran, 1999, pp. 16, 28) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: še8 = see šéš, še10 = excrement, dung

[95] šè: n., portion (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 16) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: šè = portion or part.

[96] še7 = voir šèñ = šeñ3,7, še7 = rain; to rain (šu, ‘to pour’ + to mete out) (A.Halloran, 1999, pp. 16, 28) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: še7 = see šèñ = šeñ3,7, še7 = rain, pleuvoir (šu, ‘to pour’ + to get).

[97]a, e4 = noun. water; watercourse, canal; seminal fluid; offspring; father; tears; flood (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 3) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: a, e4 = nominative = water, watercourse, canal, seminal fluid, offspring, father, tears, flood.

[98] eššu: ear of barley or other grain (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 3) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: eššu: ear of barley or other grain

[99] “éše” or “eš”: anointing oil, tomb

éše” or “eš” refers to anointing oil, which in ancient times was used to designate a king or queen. Indeed, the Sumerian word “Ereš” for Queen necessarily comes from the use of anointing oil (with “Er” the one who leads, conquers and “eš” the anointed one), that at the tomb “eš” as in ereš, ereç? (ideographic sign Nin) which means “the Queen, the lady” (and also the one with knowledge, the intelligent one, ereš5) and which enters into the composition of the name of the Sumerian goddess queen of the dead, Ereškigal, the queen of Kigal, of the “great land” synonymous with the Sumerian kingdom of the dead.

[100] Cereal ear with occurrences in: it father; barley, cereal (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 39) ; knowing that iti father (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 39) and ity itiw it tiy sovereign, monarch (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 39)

[101] anše = male donkey; onager; equid; pack animal (an,’sky; high’, + šè, terminative postposition = ‘up to’ = ‘towing raise up, carry’) [ANŠE; KIŠ] (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 51) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon: anše = donkey; evening primrose; equine; beast of burden (an “sky, high” + šè, final ending = “up to” = towing, raise up, carry) [ANŠE; KIŠ].