PURPOSE OF THIS ARTICLE

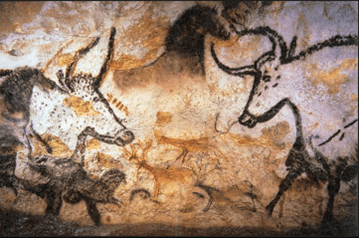

This article will translate the meaning of the bull / auroch fresco with its signs, into the proto-Sumerian ideographic language and its associated languages: Sumerian and Hieroglyphic. He proves that this is the great prehistoric divinity and reveals his name.

Table of contents

LINK THIS ARTICLE TO THE ENTIRE LITERARY SERIES “THE TRUE HISTORY OF MANKIND’S RELIGIONS”.

This article is an excerpt from the book available on this site:

You can also find this book at the following link :

To find out why this book is part of the literary series The True Stories of Mankind’s Religions, go to page :

Structure and content

I hope you enjoy reading this article, which is available in its entirety below:

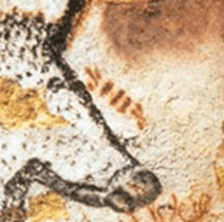

Lascaux cave: The first bull on the Unicorn sign

You’ll no doubt recall that this sign is present on the first fresco, and is found almost at the end of the run, at the level of the feline diverticulum before the last figures in the basement and the arrival at the apse and well.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grotte_de_Lascaux#/media/Fichier:Lascaux_painting.jpg

Feline diverticulum. Panel I. The “XIII”. Diagonal cross and triple parallel line, painted in black at the bottom of a niche on the west wall.

What does it mean?

This sign (noted as 92A in the comparative table in the appendix) is found in both proto-cuneiform [1] : than in hieroglyphics :

To understand this sign, we must first understand what I i.e. a single stick means.

The I sign

In proto-cuneiform

, a single line means a or e[2].

But what does “a” mean in Sumerian?

a means a father, a watercourse, etc. [3]. Add to this the fact that in Sumerian the phoneme “i” also means a watercourse by i7[4].

We can thus understand how a single line can designate the father, notably through the symbolism of the river.

In hieroglyphics

The simple vertical line

Its polysemous meaning is just as profound and important. [5]

The single lineis used to designate “the one, the only” as in the hieroglyphic wa

« one; the only one, the only one”, a qualifier that is notably matched by its equivalent, waty used to designate the great divinity under his avatar sbA waty « the morning star, the planet Venus »[6] when she reappears regenerated after her death. This Venus god is the counterpart of the Egyptian black sun, i.e. the same great divinity during her death and passage through the underworld.

is a sign that was also used as a substitute for hieroglyphic human figures, so as not to have to pronounce them out of superstitious fear of their magical power, since they were great deities.

Interestingly, it can also mean « i », « me, I ».

We also find in the lexicon the fact that the i (with the determinative of “broom / bush”) means “me, I” (or even the broom / bush alone).)[7]

Concerning the i, note that in Egyptian, it is interchangeable with A.

There are many examples[8].

And since a means “father” in Sumerian, the elder sister language of Egyptian [9],

This “i” also symbolically and culturally conveys the meaning of “father”.

Finally, the simple vertical line can also replace the hieroglyphic form

the figure of man”: which is written

« s ».

What do we understand?

That culturally, symbolically, this simple stroke that can be vocalized i,

but also A, designates a man, a father, deified under the great main deity, the only god.

As we shall see in Part II, from God to Adam, this is why « s » or « sa » is to designate man, and first and foremost, primordial man.

The single horizontal line

The horizontal variant of the simple vertical line is just as interesting. [10].

In fact, it is used only in the hieroglyphs diwt which means “a piercing cry; a howling, a bellowing”.

Now, if we know Sumerian, this “cry” speaks to us, or rather screams at us, because it screams the word “father”.

Indeed, one of the words for father in Sumerian is ada, ad, which means not only father, but also a cry [11]…

On the other hand, Egyptian dniwt by virtue of the elision of the w [12] is a homophone of dnit, which designates a channel. [13].

A channel we know from Sumerian to be a symbol of the father.

We thus find associated with this simple horizontal line (a variant of the vertical), the symbols of a shouting father, of a bellowing bovid…

The fact that we find it tripled opposite the first bull in the unicorn fresco is no coincidence…

If you doubt that this is the primordial father, let’s take a look at the meaning of the single diagonal line.

The single diagonal stroke

This sign or

is equally explicit [14].

In fact, apart from the fact that it is also a substitute for human figures referring to deities whose names must not be pronounced for superstitious fear of their magical power, this sign also serves to replace the hieroglyphic which, as you can see, refers to an old man with his old-age stick.

Indeed, it is used in to replace

which are both vocalized indistinctly smsw a term that designates “an elder, the most ancient, the eldest”.

Clearly, the deity to whom this feature refers is none other than the deified ancestor of mankind, primordial man.

It’s not a question of an all-powerful god, who has always been so, exercising his dominion from the symbolic “sky”, but of a mâne, i.e. a human ancestor who was deified after his death.

The sign of two single oblique or vertical lines

While we’re on the subject, let’s see what the two oblique or vertical lines in Egyptian have to tell us:

In fact, they illustrate the same aspect we’ve already mentioned: the fact that they serve as substitutes for the representation of deities.

Indeed, that in certain cases replaces human representations considered magically dangerous [15], with the example of the hieroglyph

to replace

which are all vocalized Axt(i) and refer to “the two glorious ones”. These “two glorious ones” allude to Nekhbet and Ouadjet, the vulture and serpent goddesses protecting Upper and Lower Egypt.

The hieroglyph Axt is also the name of the goddess Akhet and the hieroglyphic Axt designates the king’s tomb as an inhabitant of the horizon [16], to which it should be added that Axty

an “inhabitant of the horizon” is in fact an epithet of divinity [17].

We thus understand that this sign of two inclined or vertical lines designates a major divinity, a god-king, or a goddess-queen.

The III sign

In proto-cuneiform

In proto-cuneiform we find the sign or

What does this mean?

Let’s see how Sumerian’s younger sister language, hieroglyphic Egyptian, can help us.

In hieroglyphics

The Z2 vertical triplet line

In hieroglyphics, this sign

is used as a determinative to indicate “to multiply by three” or the plurality three.

Once again, this sign was used as a substitute for human-figure hieroglyphs, so as not to have to pronounce them out of superstitious fear of their magical power, since they were about great divinities.

In fact, in the Middle Kingdom, this sign was integrated into the hieroglyph… wrw which designate “the great ones”, i.e. “the gods” of a region [19]

We then understand that this sign is in fact a sign of the plural of majesty assigned to the (greatest) divinity or supreme deity.

If a single stroke, or even two, already represents great divinities, repeated three times designates the supreme deity.

This plural of majesty is the same principle we find in Genesis with the term Elohim, which some translate as gods, as if God were plural, generally to support the doctrine of the Trinity. This fails to understand that this form, even if plural, serves to emphasize the supremacy of the God in question, and not his real threefold nature, especially since, as we have already seen, the unique trait means that he is the only one. The triple repetition of this fact does not, therefore, lead to its demultiplication, but on the contrary serves only to emphasize that he is the only one of all, in other words, the only supreme God.

If the single stroke is therefore “i”, the “me, I”, the triple stroke is “we”, a bit like the king who says “we” when speaking of himself and his decisions in the first person plural. Again, this “we” does not mean that the king is either plural or trinitarian, but that he is the supreme authority in his kingdom.

The three superimposed lines Z3 and Z3A

When superimposed or

, these two signs have the same use as

.

Ce signe est surtout intéressant, car on le retrouve dans iAt a mound, a knoll, a hillock [20]. The fact is that iAt also means ruin

and we are referred to its synonym : AA

designating a pile of rubble, a ruin[21].

Now, as we shall see in Part II from God to Adam, this pile of rubble, this ruin, this AA designates none other than the primordial human ancestor in his corpse state.

For now, let’s simply say that a-a is another Sumerian name for “father”[22].

The result is thatthrough

or

refers again and again to a father.

The three inclined lines Z2C

This signa le même emploi que

.

It is interesting to note [23] that it is used in the hieroglyphic transliterated into awt which means herds including (large) cattle and whose hieroglyphic variant awt

means “men”.

In Egyptian, man, or men, are the namesake of large cattle. It’s logical, then, that they should be represented by them, as in the fresco we’re analyzing…

What’s more, this awt masks the identity of primordial man, the first to be associated with a cattle animal, bovid or caprine.

Indeed, the elision of the w[24] (case already cited; cf. the simple horizontal line), awt peut se dire at ; and at, in Sumerian [25] as in Egyptian [26] is an equivalent of ad which designates… the father [27].

The three minaret features Z2A

This other sign goes in the same direction as the previous ones.

We are told [28] than is a variant of the sign

as a plural determinative.

It’s particularly interesting to note that this sign is used in rT en équivalence de which is used in rT

or

which are often the determining hieroglyphs for “men, people, human kind”.

Moreover, men, the human race, is said rmTt or rTt (also ) or rtmt

What does this confirm, other than that if is, as we have seen, a plural of majesty assigned to the greatest divinity, who was obviously originally a human being?

In demotic

As for the contribution of demoticism to this question, I draw your attention to Champollion’s alphabet primer.

In relation with the sign you’ll notice that it exists in demotic.

Note that Champollion associated it twice: :

- It associates demotic signs

to hieroglyphs

.

Now the hieroglyphic arm se translittère en « a »[30].

And the hieroglyph of the vulture transliterates into « A »[31] [32].

- And Champollion also associates the demotic signs

to hieroglyphs

Now, the double reed is the hieroglyph transliterated as “y” (long consonant or vowel, as in French). The double reed is itself a doubling of the single reed

which transliterates as “i“. In Egyptian, “i” is regularly interchangeable with A. There are many examples [33]…

His script also includes the arm which transliterates into a.

So that with these equivalences too, can be transliterated as a or AA.

What does all this tell us?

That, with no contest,the signin demotic refers to « a » or « AA » (even through y).

And in the Sumerian language, the elder sister of Egyptian, this « a[34] » or « a-a[35] » désigne le père.

What’s more, if you take an interest in demotic yourself, what do you find in it that relates to the ?

This sign does in fact exist, and is noted and transliterates into y [36].

Like i, the simple vertical line, it can have the meaning of “me ; I” in the first person singular:

But what is of particular interest to us is that it also serves to introduce a magical name, a divine name, as with yt [38] « which means my divine name is…” (note in passing that this yt demotic has a hieroglyphic counterpart it which means father…) or with

(read y…A) or with

(read y.a) !

Conclusion on III

In other words, when you seethat you transliterate Y and that you can pronounce Y, a or AA, you know that you are introducing a “magical” name, a name of divinity, in this case the name of the supreme divinity with its plural of majesty and who was once a human, a father, an elder, the most ancient: primordial man

What kind of name is it?

Let’s find out.

The sign around sign III

You also noticed the same sign arranged on either side of the sign above the auroch’s mouth on the first unicorn panel

:

apport du hittite hiéroglyphique

I’d like to draw your attention to the fact that in Hittite hieroglyphics, the signis used to designate an animal [39].

Attached to the sign which designates the deified primordial father, confirms the fact that he is represented here in animal form, in this case that of the auroch.

The contribution of demotic

However, a closer look reveals that this sign is more of a dot-dash-dot type than a three-point triangle.

From this point of view, demotic allows us to better understand the meaning of what is being said here.

Indeed, while y…A introduces a divine name, as we’ve just seen, its inverse, Ay, is written as , but also

means “to praise”. [40].

(Note in passing that Ay is an equivalent of hy, which also means “to hail”, as we’ll see later.)

[41])

Both forms of Ay mean “praise” or “may it be praised”, after which follows the name of the god to be praised.

Now, you’ll notice that the A is made up of a line/dot which evokes the sign placed before and after it.

Perhaps you’re wondering what the opposite dot means?

It’s actually quite simple if you know demotic.

Re (the god ra) is written as .

(as in [or

or

] which transliterates

i.e. Re [t] of both lands [42] [the t after Re indicates a female deity, here for the goddess of Armant]).

What can you read when you see ?

« Praise Re, the lord of the two worlds (the fact that the dot is above and below also means that he is the king of heaven [above] and hell [below]). »[43]

But what is the unpronounceable name that follows this introductory formula?

The unpronounceable name of this auroch god !

I’m perfectly aware that what you’re about to read with me now will burn the lips of many readers, but we need to read this figure in its mother tongue.

We’ve managed to identify the meaning of .

It’s vocalized a or AA, and as it’s basically a triple i/A, it’s a plural of majesty to designate the father of fathers, the primordial ancestor, the first human, who was divinized in the symbolic animal form of the auroch, as the father of the gods, the greatest divinity, whose name is unpronounceable by his devotees for fear of the terrible magical consequences that the mere utterance of his name could cause them, hence the need to substitute these signs, which would otherwise have represented a man-god being.

We’ve already seen that the Sumerian “a“, which means father, also has the equivalent a-a, which also means father, as well as ada, or ad.

Knowing this, and also knowing that, as we’ll see later, in proto-languages including proto-cuneiform, animal figures are as much a part of language as signs, and are therefore usually pronounced, let’s simply ask: how do you say “auroch” in Sumerian?

Adam(a)

Here is what we read in the Sumerian Halloran lexicon [44] :

áma, am = « wild ox or cow (aurochs) » which translates as “wild cow or ox (auroch)”.

If you put ada/ad on one side and áma/am on the other, what do you read? ?

adam or adama.

I fully understand that this name is completely unpronounceable to scientists who have compartmentalized the whole of human history into totally disconnected slices and sections (not to mention their total disregard for the events of biblical Genesis), just as it was unpronounceable to their prehistoric devotees.

Even if, as we understand it, this name is not to be pronounced by either of them for exactly the same reason.

Although, in both cases, this impossibility will be just as religious in nature, since the scientists won’t be able to pronounce it (just yet), as it would infer from their point of view a total and fundamental questioning of their entire dogma.

Yet all we’ve done is read an ideographic script, in this case proto-cuneiform, which gives us the name of this auroch deity, this wild bull god, “ad(a)- am“, the “father auroch”.

Other pronunciations of the god auroch’s magical name

In this section, we’ll see how this name is also pronounced, notably in Sumerian, but also more incidentally in Egyptian hieroglyphic and Hittite, which will confirm its meaning, and enable us to understand that the auroch, wild bull, ox is a symbol, a most archaic allegory of humanity’s primordial ancestor, divinized.

the Sumerian A – gu(d) (ku ; a-ka ; ugu)

It’s imperative to understand that just as áma, am designates a wild ox or auroch, there’s another logogram with an almost identical meaning.

This logogram is the logogram “gu” which by gu4 and its strict equivalent, “gud“, designates a (domestic) ox or bull [45].

Thus, the sign III followed by the auroch symbol, the wild bull, can also be perfectly read as follows a-gu (or a-gud)

The implications of this simple fact are almost as important as the meaning ada-am(a) in explaining the constant mythological allegory primordial man-ox-bull.

To understand this, we need to remember that the consonants “g“, “k” and “ñ” are perfectly interchangeable.

We saw in the initial paragraph on the pronunciation of transliterated Sumerian consonants and vowels that there are many examples of this equivalence between “g“, “k” and “ñ“.

What does this imply?

That gu is a strict equivalent of ku.

And what does ku mean?

The meaning of ku

The term “ku” designates a biological procreative ancestor:

Indeed, the ideogram ku is said ugu4 which has the verbal meaning of “to bear, procreate, produce” »[46] [homophone of « úgu »[47] equivalent of “a-ka »].

ugu4 (and ùgun) also has the verbal sense of “to beget, to bear”, the nominative sense of “an ancestor”, an ancestor whose genetics we inherit [48]. The term ama-ugu, which combines the terms “ama” and “ugu“, means “a natural or biological mother”. »[49].

ugu therefore also has the meaning of natural, biological.

The ideogram ku is also called a-ugu4 [strict equivalent of “a-ka“], meaning “the father who begat someone” »[50].

So the ideogram ku and its phonetization in ugu or a-ka means a biological procreative ancestor, male or female.

This is also why it is repeated : “kuku” means “a founding ancestor”»[51]

Meaning of a-gu/ku or a-aka or a-ugu

Having understood that gu is a strict equivalent of ku, a-ka and ugu, all of which designate a male or female biological procreative ancestor, what sense do you now see in adding the triple III, a, a-a or AA before these logograms?

This is easy to understand, since “a” refers to a father [52], this allows us to genrate (in addition to III) this great primordial divinity under the auroch, the wild bull, the ox, as the biological, natural procreative ancestor father, the equivalent of ada-am(a).

the Egyptian

How would hieroglyphic Egyptian pronounce such a figure?

To find out, let’s take a look at the Egyptian words for ox and bull :

The beef gw, ngAw, iwA

gw

Beef can be said « gw » (pronounced gu) which designates a breed of bull, a long-horned bull or ox. [53] [54].

This gw (gu) Egyptian is therefore perfectly redundant with the Sumerian we have just seen : gu4 (like its equivalents, gud, guð) which also designates a domestic ox, a bull [55].

ngAw

We can also mention ngAw[56]

which means “a bull or ox with long horns”.

In connection with this word, it should be noted that the Egyptian “ng” is the equivalent of the Sumerian “ñ“.

And since the consonants “g“, “k” and “ñ” are perfectly interchangeable, ngAw reads ñAu or gAu or kAu, which is understandably phonetically very close to Sumerian “gu“. This is all the more the case as in Egyptian, the A is often elided. [57].

ngAw can therefore also be transliterated gw

in Egyptian, which is the reason for its equivalence in meaning with it.

As a result, in Egyptian too, this figure can be perfectly read as a-gw as in Sumerian.

This is one of the many proofs of the entanglement that we shall observe between Sumerian and Egyptian hieroglyphics, an entanglement that will enable us to understand the profound meaning of Egyptian mysticism, and that allows us to understand that the meaning to be given to this Egyptian a-gw is strictly the same as the Sumerian meaning.

iwA

Another way of saying ox in hieroglyphic Egyptian is iwA designating an ox or, more generally, cattle with long horns [58].

But who can perfectly designate this ox, iwA?

The father, the ancestor, the old man, the triple AAA, who was the object of adoration.

Why is this also true in Egyptian?

For two perfectly complementary etymological and therefore symbolic and cultic reasons:

iwA= AA

Note that iwA can be said “AA“, as “iw” in Egyptian may be equivalent to “A” at the beginning of a word. [59] !

From this etymological angle, iwA the “ox… with long horns” is by AA the equivalent of the Sumerian father a-a.

But he’s also the grandfather, the old man.

Let’s see why:

iwA = iAw

The fact is that iwA can also be said iAw in Egyptian by virtue of the consonantal inversion that is sometimes observed [60] such as iAm, imA (the hieroglyph for tree iAm is a variant of the hieroglyphic

imA [which also means tree]: where the meanings are strictly equivalent, although the last two letters are reversed).

What does iAw mean? ?

iAw [61] means “an old man”.

An old man who is clearly the object of adoration, since iAw‘s hieroglyphic homophone is iAw which means adoration…

In addition, iAw can also be written as iAa or iaA [62].

And iAa is also written AAa, in accordance with the often observed Egyptian rule whereby the initial “i” is interchangeable with an A [63]

We therefore find ourselves faced with the Sumerian “father” “a“, or rather the Sumerian grandfather “a-a-a” (with the word father redoubled in a [64] a-a[65] hence the grandfather, the old man).

So, iwA, the long-horned ox, the auroch, is simply the inverted mirror of iAw, the Egyptian old man, equivalent to AAa in Egyptian, equivalent to a-a-a the Sumerian grandfather, who was the obvious object of adoration and to whom, as his name implies, we can attach the triple Egyptian, the plural sign of majesty specific to the great divinity.

The Taurus kA, the ox skA

Now let’s see how bull or ox can also be said in Egyptian. :

kA

It can be saidkA bull, ox.

This logogram kA is strictly the same as the hieroglyphic kA which designates the « Ka » i.e., the “soul, spirit” of a being in Egyptian religion [66].

The fact that kA designates both a soul and a bull or ox shows the intimate association between the two in Egyptian thought.

We’ll have plenty of opportunity to illustrate in subsequent books how, in Egypt, the father of the gods was repeatedly reputed to have been incarnated in an ox-bull kA, hence the cult that would be worshipped in Egypt (and in virtually all other mythologies) to sacred oxen or bulls incarnating the avatar of the local father of the gods.

skA

Finally, note that the hieroglyphic skA means a plough ox [67].

But what does “s” mean in Egyptian?

« s » designates a man, a man of high rank [68].

So this s-kA, this ox in ploughing is etymologically and symbolically an incarnation of the soul of a kA being of a human, a man of high rank« s ».

Findings

All these Egyptian words we’ve seen (gw, ngAw, iwA; kA, skA) convey together the idea of the soul of the grandfather, the old man worshipped as the great divinity marked with the plural of majesty and embodied in an ox-bull.

These logograms are equivalent to the Sumerian logograms gu / ku (a-ka / ugu).

It’s a perfect match for :

- the Sumerian a-ku father “a” ancestor-generator-creator “ku / a-ka / ugu” represented under “gu, gud” by the imagery of the ox, the bull, as the father of the gods and the great divinity

- the ad(a)-am, the father auroch.

the Hittite a-ga

I also find it interesting to observe how a Hittite, whose semiological system, as we’ve seen, mixed elements of Sumerian and Egyptian hieroglyphic, would pronounce this representation of a bull.

One thing is certain: he would pronounce the bull “ga“.

Why would he do this?

Just look at the Hittite cuneiform syllabics I mentioned in part one: the scientific semiological demonstration :

ga = = a bull (wounded ?)

Take another look at how hieroglyphic Hittite represents the syllable a: with the figure of a man

So if a Hittite pronounced aga or heard a Sumerian pronounce aga, which is, as we have seen, a strict equivalent of a-ka, ugu, ku, this would immediately conjure up in his mind the imagery of a man-father-bull, with all the underlying Sumerian and Egyptian mysticism that I have developed..

Conclusion

Thus, proto-cuneiform, Sumerian, hieroglyphic (and more incidentally hittite cuneiform and hieroglyphic) concur to demonstrate that this auroch introduced by the double sign and the triple

can be translated (using Sumerian transliteration only):

« Praise Re, lord of both worlds »

III « We, the supreme god, whose divine name is… »

- adam(a): III “ad(a) / a-aa, the human father, the grandfather, the old man” áma, am the auroch, the wild bull

- a-aa-ku/gu: III “ad(a) / a-aa, human father, grandfather, old man” ku (a-ka, a-ga, ugu) biological procreative ancestor, gu ox, bull

NOTES ET RÉFÉRENCES DE BAS DE PAGE

[1] 92A (Falkenstein, 1936, pp. 88, 97, 124)

[2] 90A (CNIL, p. 94) ; (Falkenstein, 1936, p. 341)

[3] a, e4 = nom. : water; watercourse, canal; seminal fluid; offspring; father; tears; flood (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 3) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon: a, e4 = nominative = water, watercourse, canal, seminal fluid, descent, father, tears, flood or deluge.

[4] ída, íd, i7 = river; main canal; watercourse (éd,’to issue’, + a,’water’) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 18) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon : i7= (cf., ída) —) ída, íd, i7 : river, main canal, watercourse (ed ” generate + a “water”).

[5] The Z1 sign: Sources : https://www.hierogl.ch/hiero/Signe:Z1 ; Gardiner p. 534, Z1

It is used as a determinative in the one, the unique, the only: wa one; the only one, the only one see also wai

to be alone (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 70).

This sign was used (as

and ° )

to replace human figures, considered magically dangerous; e.g. on M.E. sarcophagi.

Rarely, extensions of this usage appear in the use of as a suffix of 1st pers. sing. “i” je, moi; perhaps also in the fairly common writing of

to replace s

or

or

man

[6] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon : waty unique, alone waty, wat

captive, prisoner waty

goat ; sbA waty

the lone star = the morning star (planet Venus) (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 70)

[7] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon: i reeds (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 9)

used infrequently (“encrypted writing”) to i I, me hence

[8] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon: / “i” / rule that “i” is sometimes identical to “A” at the beginning of words. For example:

ims show concern (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 26) vs Ams

show concern / (Gardiner, p. 58)

irt eye (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 31) vs Axt

eye (of a god) (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 5)

ihm to be sad (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 33) vs Ahmt pain, grief, sorrow, sadness (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 4)

ixxw iwxxw

axxw

twilight, dusk; dawn, daybreak (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 35)

iHA to fight, to combat; combat ; (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 34) variant of aHA to fight, to combat; combat(Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 57)

iAwt old age ;

small livestock; herds(Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 10) vs Awt

small livestock; herds (voir IAwt)

Etc…

[9] Later in this book, and in Part II from God to Adam, we’ll see evidence of the linguistic entanglement between Sumerian and the language of hieroglyphs.

[10] Horizontal single stroke Z1A / Sources : https://www.hierogl.ch/hiero/Signe:Z1A

This is a variant of

in a horizontal position.

Its two recorded occurrences are in diwt :

diwt Team of 5 and in diwt

« shriek; howl, bellow” a variant of dniwt

« shriek; howling, bellowing » (https://www.hierogl.ch/hiero/dniwt)

[11] ada, ad : n., father; shout; song. v., to balk. (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 18) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French Lexicon = ada, ad = nominative: father, cry, song / verb: to complain

[12] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French Lexicon / elision of the w: If we take into account the rule that, in certain cases, the ou sign (w/u=ou) is superfluous. According to Coptic, it should not be pronounced, Gardiner p. 52, §59.

Here are a few examples:

iwf (if) flesh; meat; fish flesh (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 16); reads if. The sign

or

is superfluous according to Coptic, and should not be pronounced, Gardiner p. 52, §59. See also if

flesh; meat; fish flesh (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 21)

imyw-mw Cf. imy which is in and mw water (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 22)

imyw-tA snakes (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 23)

Cf. imy which is in and tA earth

Hwtt mine, quarry; variant of Htt mine, quarry (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 205)

abwt function stick; hay fork (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 50) vs abt

attachment, bond

a funerary ritual object

fork-shaped stick; variant of abwt fork-shaped stick (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 50)

[13] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon : dnit dam, dike

ditch, canal

terrine, écuelle panier, corbeille

a party (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 387)

[14] Single diagonal line Z5A ; Sources : https://www.hierogl.ch/hiero/Signe:Z5A

diagonal line according to hieratic design (sometimes also

)

Identical to original with line used under Pyr. as a substitute for human figures, these being considered magically dangerous, e.g. smsw

to replace

eldest, the oldest; the eldest; also smsm (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 282)

[15] The two oblique or vertical lines ; Sources : https://www.hierogl.ch/hiero/Signe:Z4 ; Gardiner p. 536, Z4 . See alsoGardiner p. 59,, §73,4

Two oblique lines, less often vertical :

:

In some cases replaces human representations considered magically dangerous, e.g.

Axt(i) les deux glorieuses to replace

[16] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon : Axt Akhet (the goddess) ;

arable land ;

uræus snake ;

eye (of a god) see irt

eye (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 31) ;

flame ;

horizon, king’s tomb/ (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 5)

[17] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon : Axty inhabitant of the horizon; residing on the horizon (idiom.), an epithet of god / (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 5)

[18] 92A (Falkenstein, 1936, pp. 88, 97, 124, )

[19] The sign Z2 : Sources : Gardiner p. 535 ; https://www.hierogl.ch/hiero/Signe:Z2

Stroketripled. It also says

or

det. of plurality, common from the 9th dyn. on, after an ideo. or det. to indicate that it must be understood three times

The use of as a plur. det. cannot be entirely dissociated from the use of

and ° in Pyr. as substitutes for signs representing human figures considered magically dangerous; in M.E. it is also found with purely phonetic signs, e.g. wrw

the greats (the gods of a region)

[20] The sign Z3 ; https://www.hierogl.ch/hiero/Signe:Z3 ; Source Gardiner p. 536, Z3

Same as

Common in hieroglyphic since 12th dyn., rarer in hieratic, where the original form was

https://www.hierogl.ch/hiero/Signe:Z3A : As for this is the original form of the sign

in hieratic writing. With Same use as

we find in iAt knoll, mound, hillock ; iAt also means ruin

. See also AA rubble heap, ruin

[21] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon : AA : Rubble heap, ruin / (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 1)

[22] a-a : father (reduplicated ‘offspring’). (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 71) ; Volume 4 / Lexique sumérien-français = a-a : père (redoublement de « descendance »)

[23] https://www.hierogl.ch/hiero/Signe:Z2C

même emploi que

as a plural determinative. We find

in awt

which has the meaning of herds, small livestock; goats; (large) livestock, livestock and also of “men” by the hieroglyphs

[24] Rule already quoted: see Horizontal single stroke, Vertical single stroke

[25] Volume 4 Sumerian Lexicon / Consonant equivalents: The letters

“d” and “t” are sometimes equivalent. An example is the logogram “dú”, which is a strict equivalent of “tu”:

tud, tu, dú = to bear, give birth to; to beget; to be born; to make, fashion, create; to be reborn, transformed, changed (to approach and meet + to go out) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 24) ; Volume 4 / Lexique sumérien-français = dú = tud = tud, tu, dú = porter, donner naissance à ; engendrer ; être né ; faire, façonner, créer ; être né de nouveau, transformé, changé (approcher et rencontrer + sortir).

[26] The d / t equivalence can be seen in Egyptian with, for example :

Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon

: At an aggressor (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 8) variation of Adw

an aggressor / (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 8)

[27] Reminder : ada, ad = n., father; shout; song. v., to balk. (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 18) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon : ada, ad = nominatif : père, cri, chant / verbe : rechigner

[28] Source : https://www.hierogl.ch/hiero/Signe:Z2A : is a variant of the sign

. It has the same use as a plural determinative. It is found in rmTt ou rTt

men, human kind; also

or rtmt

; The determinatives for men, people, human kind are

often written rT

or thus

(The latter is a good example).

[29] Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens, ou, Recherches sur les éléments premiers de cette écriture sacrée, sur leurs diverses combinaisons, et sur les rapports de ce système avec les autres méthodes graphiques égyptiennes. (Édition révisée avec lettre à Mr Dassier). Champollion Le Jeune

[30] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon: a arm, hand; region, province; condition, state; item, part; track, trace (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 45)

[31] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon : A = Vulture / (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 1)

[32] Reminder: See Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon / transliteration : « A » = (vulture) = pronunciation: [ʔ], hamza (“glottal blow”) as in Arabic.

[33] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon: / “i” / rule that “i” is sometimes identical to “A” at the beginning of words. For example:

ims show concern (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 26) vs Ams

show concern/ (Gardiner, p. 58)

irt eye (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 31) vs Axt

eye (of a god) (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 5)

ihm to be sad (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 33) vs Ahmt pain, grief, sorrow, sadness (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 4)

ixxw iwxxw

axxw

twilight, dusk; dawn, daybreak (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 35)

iHA to fight, to combat; combat ; (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 34) variant of aHA to fight, to combat; combat (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 57)

iAwt old age ;

small livestock; herds (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 10) vs Awt

small livestock; herds (voir IAwt)

Etc…

[34] a, e4 = nom. : water; watercourse, canal; seminal fluid; offspring; father; tears; flood (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 3) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French glossary : a, e4 = au nominatif = eau, cours d’eau, canal, fluide séminal, descendance, père, larmes, inondation ou déluge.

[35] a-a : father (reduplicated ‘offspring’). (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 71) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon = a-a : father (repetition of “descent»)

[36] https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/publications/demotic-dictionary-oriental-institute-university-chicago / III, Y

[37] https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/publications/demotic-dictionary-oriental-institute-university-chicago / III, Y ; p.1

[38] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French glossary: it father ;

barley, cereal (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 39) ; iti

father (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 39)

[39] Cf : Go to :

https://mnamon.sns.it/index.php?page=Scrittura&id=46

And to : https://www.hethport.uni-wuerzburg.de/luwglyph/ –) sign list. p. 15 signe référence 404

[40] À is written in demotic, but also often

in final form, or

[41]https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/publications/demotic-dictionary-oriental-institute-university-chicago / H, p.8

[42] https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/publications/demotic-dictionary-oriental-institute-university-chicago / R, p.22

[43] In the expression Re-tawy, it’s the wy that is the duel mark; the notion of duality in Re’s kingship, on the other hand, is implied by the position of the dot on either side of the stroke, in addition to the fact that stroke-dot, as we’ve seen, means praise. The expression I use of “lord of the two worlds” does not therefore come from tawy, which is written differently.

[44] áma, am = wild ox or cow (aurochs) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 19) ; Volume 4 / Lexique sumérien-français = áma, am = vache ou bœuf sauvage (auroch)

[45] gud, guð, gu4 = n., domestic ox, bull (regularly followed by rá ; cf., gur4 (voice/sound with repetitive processing – refers to the bellow of a bull) v., to dance, leap (cf., gu4-ud). (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 23); Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon : gud, guðx, gu4 = bœuf domestique, taureau (régulièrement suivi par rá ; cf., gur4) (bruit récurrent qui fait référence au mugissement du bœuf. Verbes : danser, sauter (cf., gu4-ud).

[46] ugu4 [KU] = to bear, procreate, produce (cf., ugu4-bi). (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 18) with translation in Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon : úgu4 (KU) = porter, procréer, produire (cf., ugu4— bi).

[47] a-ka = (cf., úgu) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 72)

[48] ùgun, ugu4 = n., progenitor. v., to beget, bear. adj., natural, genetic (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 68) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon : ùgun, ugu4 = nominatif ancêtre, progéniteur /verbe : engendrer, porter. Adjectif : naturel, génétique.

[49] ama-gan; ama-ugu = natural or birth mother (‘mother’ + ùgun, ugu4, ‘to beget’) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 77) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon : ama-gan, ama-ugu = mère naturelle ou biologique (« mother » + ùgun, ugu4, « engendrer »).

[50] a-ugu4 [KU] = the father who begot one (‘semen’ + ‘to procreate’) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 74) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon = a-ugu4 (KU) = le père qui engendra quelqu’un (« sperme » » + « procréer »).

[51] ku-ku: ancestors (?) (‘to found; to lie down’) (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 113) ; Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon : ku-ku = ancêtres (?) (“fonder”).

[52] a, e4 = nom. : water; watercourse, canal; seminal fluid; offspring; father; tears; flood (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 3) with translation in Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon : a, e4 = au nominatif = eau, cours d’eau, canal, fluide séminal, descendance, père, larmes, inondation ou déluge.

a-a : father (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 71) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French syllabary : a-a : père

[53] https://www.hierogl.ch/hiero/Signe:Z9 : the prototype of

has become

. The latter replaces many obsolete determinatives and takes their place in the : Hs

excrement sin

clay wHAt

cauldron mAt

granite Abw

Elephantine gw

breed of bull from which dét. phon. gA. It is also a determinative of aS

parasol pine

[54] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon : gw breed of bull; cf. ngAw

long-horned bull or ox (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 353)

[55] gud, guð, gu4 = n., domestic ox, bull (regularly followed by rá ; cf., gur4 (voice/sound with repetitive processing – refers to the bellow of a bull) v., to dance, leap (cf., gu4-ud). (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 23); Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon : gud, guðx, gu4 = bœuf domestique, taureau (régulièrement suivi par rá ; cf., gur4) (bruit récurrent qui fait référence au mugissement du bœuf. Verbes : danser, sauter (cf., gu4-ud).

[56] Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon : ngAw long-horned bull or ox (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 176)

[57] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon / observable rules / elision of the A: Here are some examples of elision of the A in different hieroglyphs:

hAbq to grind, to triturate, to shell; variant of hbq to grind, to triturate, to shell

hw neighborhood, surroundings

kinship, close relations, entourage; variant of hAw kinship, close relations, entourage

ikb mourning; variation of iAkb mourning.(Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 38)

fqA a cake fqA

fqAw (plural)

fq

reward, reward, remunerate; reward, reward, remuneration, remuneration, salary(Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 122)

Drt* hand; trunk; loop See also DAt hand

prejudice, harm; lamentation; * reads Drt not drt or dt.

[58] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon : iwA ox; long-horned cattle ;

beef meat (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 15)

[59] « A » may be equivalent to « iw » :

iwms inaccuracy, lie (Faulkner, reed.2017, p. 16); iw-ms, lit. arrangement of what is; see Ams: Ams

lie / (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 4)

[60] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon / observable rules / Am, mA type inversion: Here are some examples in different hieroglyphs:

imA tree; kind; well-disposed; pleasant; to be full of grace; to be enchanted (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 24) cf iAm

; iAm : tree (imA tree variant) (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 11)

imAw, imw, iAmw radiance, splendor

tente, hutte (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 24)

[61] See volume 3 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon : iAw adoration ;

old man (Faulkner, réed.2017, pp. 9,10)

[62] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon / observable rules / equivalence aw, Aa, aA : iaw wash (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 13) where Faulkner’s lexicon refers us to iAa, iaA

skirt, apron ;

wash; leach, erase ; (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 13)

[63] Review note already quoted Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon / observable rules / rule that “i” is sometimes identical to “A” at the beginning of words, with numerous examples.

[64] a, e4 = nom. : water; watercourse, canal; seminal fluid; offspring; father; tears; flood (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 3) with translation in Volume 4 / Sumerian-French lexicon : a, e4 = au nominatif = eau, cours d’eau, canal, fluide séminal, descendance, père, larmes, inondation ou déluge.

[65] a-a : father (A.Halloran, 1999, p. 71) Volume 4 / Sumerian-French syllabary : a-a : père

[66] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon : kA Ka, soul, spirit ;

bull, beef (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 347)

[67] skA cultivate, plow ;

plough ox ;

crops (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 308)

[68] Cf Volume 4 / Hieroglyphic-French lexicon : s (z) door lock

ornamental container

shower of arrows

or

man; someone; no one, none, nil; man of rank (Faulkner, réed.2017, p. 255)

BIBLIOGRAPHIE

Proto-sumérien :

CNIL. Full list of proto-cuneiform signs

& Falkenstein, A. (1936). Archaische Texte aus Uruk. https://www.cdli.ox.ac.uk/wiki/doku.php?id=late_uruk_period :

Sumérien :

A.Halloran, J. [1999]. Lexique Sumérien 3.0.

Héroglyphique :

Faulkner. [réed.2017]. Concise dictionary of Middle Egyptian.

Hiero (hierogl.ch) (Hiero – Pierre Besson)

Démotique :

Hittite hiéroglyphique :

Mnamon / Antiche scritture del Mediterraneo Guida critica alle risorse elettroniche / Luvio geroglifico – 1300 a.C. (ca.) – 600 a.C.

https://mnamon.sns.it/index.php?page=Scrittura&id=46

https://www.hethport.uni-wuerzburg.de/luwglyph/Signlist_2012.pdf

REMINDER OF THE LINK BETWEEN THIS ARTICLE AND THE ENTIRE LITERARY SERIES “THE TRUE HISTORY OF MANKIND’S RELIGIONS”.

This article is an excerpt from the book also available on this site:

You can also find this book at the following link :

To find out why this book is part of the literary series The True Stories of Mankind’s Religions, go to page :

Structure and content

COPYRIGHT REMINDER

As a reminder, please respect copyright, as this book has been registered.

©YVAR BREGEANT, 2023 Tous droits réservés

The French Intellectual Property Code prohibits copies or reproductions for collective use.

Any representation or reproduction in whole or in part by any process whatsoever without the consent of the author or his successors is unlawful and constitutes an infringement punishable by articles L335-2 et seq. of the French Intellectual Property Code.

See the explanation at the top of this section. the author’s preliminary note on his book availability policy :