PURPOSE OF THIS ARTICLE

This article will help you understand why the mother goddess and the great deities were depicted in a crouching position:

The link with the belief in their power to bring fertility to the world of the living and, above all, rebirth to the dead.

We’ll also look at the close link between this representation and the symbolic category of fluids.

Table of contents

LINK THIS ARTICLE TO THE ENTIRE LITERARY SERIES “THE TRUE HISTORY OF MANKIND’S RELIGIONS”.

This article is an excerpt from the following book entitled :

A book that you can also find here :

To find out why this book is part of the literary series The True History of Mankind’s Religions, go to :

Introduction / Structure and Content

I hope you enjoy reading this article, which is available in its entirety below.

THE SYMBOLISM OF THE CROUCHING MOTHER GODDESS

This symbolism is fully in line with the major teaching of the prehistoric mythological religion at the origin of paganism, which believed that the primordial human mother, who became Mother Goddess of the Earth, was able to regenerate and give new birth to all her devotees and worshippers. Indeed, the mother goddess was reputed to have regenerated and reborn her own husband after his death, enabling him to become a deity, the father of the gods (or even to remain on earth, incarnating himself in their son to continue guiding mankind).

This symbolism of the crouching goddess is thus one of the many major matrix symbols (places and objects) used by this religion to represent the matrix of the mother goddess, symbols which are/will be exhaustively listed and analyzed in volume 3 “The Bible of symbols of prehistoric and ancient mythological religion”.

This symbolism of the crouching goddess is also closely associated with the symbolism of fluids.

By way of reminder, as also explained and detailed in volume 2, it was taught that in her capacity as mother goddess capable of regenerating the father of the gods and giving life to the son-god, since the latter had the status of messiah, guide, but also redemptive power, she came to be seen as having the son-god’s own redemptive power, and thus as being able to give not only abundance and fertility on Earth, but also, and above all, immortality in the afterlife. It’s important to understand this, because it’s the key to understanding that this belief that the mother goddess herself could confer immortality through the fruit of her womb, her flesh coming out of her womb, is what explains the belief that the direct absorption of her vital fluids by her devotees (rather than passing through the redeeming son) could confer immortality.

Thus, on Earth, its vital fluids were synonymous not only with abundance and fertility, but also and above all with the elixirs of immortality.

Here again, volume 2 will provide an exhaustive list and analysis of the various symbols used in prehistoric mythological religion to represent, in all their mystique, the different bodily fluids coming from the body of the mother goddess (we can cite here, simply as an example, the symbolism of beer, which represents the urine of the great divinity[1] ).

It’s also very important to understand that this symbolism of the crouching goddess is very closely linked to the symbolism of the hand, for, although the symbolism of the hand is one of the most polysemous, it is one of its most important symbolisms. We’ll see this time and again, particularly when it comes to understanding the rationale behind the architecture and ornamentation of many temples. This link between the crouching goddess and the symbolism of the hand will not be dealt with in this article, but in a separate one to follow.

THE LINK BETWEEN CROUCHING AND (RE)BIRTH

The simple reason why the great deity has been depicted in the crouching position when regenerating or giving birth (whether to the great god or his worshippers), or when diffusing his fluids of earthly abundance or elixir of immortality, is because, in ancient times, the crouching position was the preferred position for giving birth.

It then became natural to represent the mother-goddess in this position, not only to give birth and give to the world the fruit of her womb, the son-messiah, but also to restore life to the dead and spread her vital fluids of abundance and immortality.

Let’s take a look at some examples that demonstrate this.

THE LINK BETWEEN CROUCHING AND CHILDBIRTH

First of all, let’s look at a few examples of how the crouching position was the position of childbirth.

IN EGYPT

For example, here’s what you can read about the Egyptian goddesses Hathor and Tawaret, deities of maternity and childbirth:

“The bas-reliefs of the temple in the ancient Egyptian Complex of Dendera depict a Woman giving birth in a crouching position and in the presence of the two birthing figures, the goddess Hathor and the goddess Taweret ; Hathor was an ancient popular deity with many associations, including those of Motherhood, Fertility and feminine love, which is why the ancient Egyptians believed that this deity should preside over all births as guardian of Women and Children, like Taweret, who was also a key goddess of Fertility and Childbirth, which may explain why there are no known words in ancient Egypt for midwife, obstetrician or gynecologist”.

“Women delivered their babies on their knees, crouching, or on a birthing seat as indicated in the hieroglyphs speaking of Birth, while hot water containing Honey was placed under the seat, so that the vapors would facilitate delivery, and incantations aiding delivery were repeated by the midwives such as those asking Amun to “make the heart of the deliverer, strong, in order to keep the unborn child alive.””

“The use of the crouching position or birthing seat was a very common method in ancient African traditions and today contemporary birthing traditions also advocate the use of the crouching position or birthing seat, for the simple reason that both encourage the use of gravity as a natural aid in this process.”

Note in passing that the goddess Amamët[2] and the goddess Maât[3] are also mentioned as crouching.

So far, nothing out of the ordinary.

It was just an obstetrical practice.

But if we turn to other descriptions of deities, we’ll see that this representation goes far beyond the simple descriptive framework of a human giving birth, aided by goddesses.

As we’ve just seen in Egypt, major deities are represented in this way.

Let’s turn now to other civilizations and their imagery of local deities.

THE LINK BETWEEN CROUCHING AND REBIRTH

IN ELAM

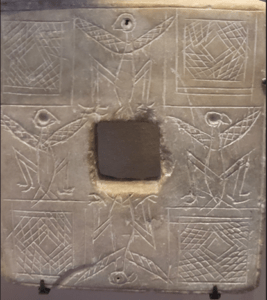

Allow me first to introduce this structure, an Elamite perforated plate found in the Louvre.

Musée du Louvre. Text from the Louvre: Perforated plate. Four eagles with outstretched wings; squared squares. Alabaster. Susa. Sukkalmah dynasty (mid-20th century-1500 BC). Source photo : Yvar Bregeant

As you can see, it’s square-shaped, with four eagles (actually vultures) crouching with wings spread on either side of a central square-shaped hole, with a striated square between each vulture.

To understand the symbolism of this plaque, you need to know the respective symbolism of the square, the perforated stone, the broken column, the pyramid, the mountain and the vulture.

If you know the meaning of each of these symbols, you’ll understand the significance of their union here.

To cut a long story short, the square here represents the mountain, which is a symbol of the mother goddess’s body.

Note that the four striated squares represent, as seen from above in perspective, pyramids with tiers rising towards the sky to indicate elevation towards the heavens. Remember then that the pyramid is strictly associated with the mountain and is also a symbol of the body of the mother goddess.

In this respect, let’s just remember that the word for mountain is šadu in Akkadian[4] , one of whose meanings is, literally, in Sumerian, ša[5] the body, the womb of the[6] that gives or restores life.

Nota Bene:

This rebirth is essentially conveyed by the homonym “dú”, equivalent to tud or tu, which means: to bear, to give birth to, to engender, to be born, to make, to shape, to create; to be born again, transformed, changed. With dú, it’s not only a question of birth, of being shaped, but also of rebirth, of transformation into a new being, an operation reputed to take place by returning to the ša, the body or womb of the mother goddess.

The perforated stone represents the broken column of primordial man, whose restoration within the pyramid represents his regeneration as father of the gods.

The vulture is one of the major representations of the mother goddess in her role as presiding over the process of rebirth after death.

Now, since we’re sticking to the symbolism of the crouching goddess, what do we notice here?

That the body of the crouching vulture goddess is a symbol directly associated with that of the pyramid, whose primary purpose is regeneration, the rebirth of the primordial father as father of the gods.

Two of the vultures even seem to lay their eggs directly in the two pyramids below her.

So there’s a close link between crouching and rebirth.

IN CRETE

Equally remarkable is the fact that in Crete, as with Hathor in Egypt, “the Great Mother Goddess, probably Rhea[7] , is depicted, depending on the period, either crouching or standing[8] “.

IN GREECE

The meaning of this crouching representation of the mother goddess can also be found in Greece.

Indeed, it should be noted that the Greek goddesses of birth or childbirth, the illythies, daughters of Hera (the name of the Greek mother-goddess), are also depicted in the crouching position, a position recognized as being conducive to childbirth. Given that Illythie can also be understood as a duplicate of Hera, we understand that the mother-goddess was also represented in a crouching position as the mother-goddess of birth and childbirth[9] .

It is therefore particularly interesting to look at the Sumerian etymology of illythia[10] .

As we shall see almost systematically, the Sumerian language underpins the entire mystical edifice of mythological religion.

De facto, it becomes abundantly clear why they were given the name Illythia.

SUMERIAN ETYMOLOGY OF ILLYTHIA

Let’s break it down into Sumerian: íli-ti-a :

ETYMOLOGY OF íli :

íl-lá[11] means an elevation and in its verbal form íla, íli, íl[12] means to lift, carry, deliver, bring, endure, endure, “…”; to be elevated; to shine; lal, lá (la2)[13] means to be elevated; to hold, elevate, carry, suspend

So, by íli, we’re not just talking about carrying in the sense of conceiving as a genitor, but also carrying, elevating (to exalt, as it were) in the sense of deifying!

In this respect, it is important to mention here that these various Sumerian logograms (íl-lá; verb form íla, íli , íl; lal, lá (la2)) are recognized as the origin of the names of the gods “Īl” and “Ēl” and are the constituent root of the Sumerian word ĪLU, which has, among other meanings, that of “god”[14] .

So it’s imperative to understand two things:

Equivalence between childbearing and definition

The first is that this Greek “illy” means “to raise, to carry” with the double meaning of :

- Not only to carry in her womb to give birth

- But also, and above all, to elevate, to take to heaven, to make it shine… in other words, to deify the object of the (re)birth in question.

Just as aka “the door” has this double meaning

It’s interesting to note that íli has the double meaning of to carry in the sense of to carry in one’s belly and to carry to the skies, as does the Sumerian aka4 which designates the frame or lintel of a door.

Indeed, just as in French we say “la porte” (from the Latin porta, “door of a city, of a monument”, which supplanted the words fores and janua), but also “porter” (from the Latin portare) in the sense of carrying a child and also in the sense of “to carry, raise, elevate”, so it is exactly the same in Sumerian.

Indeed, if aka4 in Sumerian means a doorframe or lintel[15] , its homophone a-ka has the equivalent úgu[16] whose homophone úgu4 (KU) means to bear produce procreate[17] .

Moreover, ka and ga are strictly equivalent homophones in Sumerian, and with ga6 or gùr, the Sumerian lexicon indicates that these two phonemes mean to carry, to transport, while specifying that this is the reading made by the Sumerian city of Umma for the sign íla[18] .

However, as we have just seen, íl-lá and the verb forms íla, íli, íl carry the idea of elevation in the sense of deification.

Thus, we can say that just as in French the word porte (door lintel) (aka4) also carries (!) the meaning of bearing a child, of engendering (by a-ka / ugu) it also carries by the association ka / ga with íl-lá that of exalting, of elevating in the sense of deifying!

Or, to put it another way, in Sumerian there’s a semantic chain: door – a woman who carries or procreates – to carry in the sense of elevating to the rank of divinity.

Link between “íli” “a-ka” and the first name “Eve

We’ve also seen from the analysis of Eve’s name and the symbolism of the door that aka was one of her Sumerian names as the mother of her offspring (hence the fact that the door and doorpost were one of her major emblems).

In itself, this association of ideas between íli and a-ka to designate both the fact of bearing a child and elevation to the rank of divinity can only confirm our belief that the birth provided by the Greek goddess Hera-illyria is in fact a power to allow the rebirth of a being and confer divinity on it.

And this association also lifts a part of the veil that conceals the real face of the primordial woman behind the veil of the mother-goddess Hera: Eve.

“Ili” also means to shine, to hold, to carry.

If we now return to the meaning of íli, you may also have noticed in passing that to be elevated is synonymous with to shine, to hold, to carry…

Perhaps you’ll understand better then why, at the moment of birth, as mentioned in the note on Hera quoted above, Hera-Illythia was also depicted holding a torch, symbolizing, of course, light, but also, as we shall see, the symbolism of the star of the born-again being, now a star, symbolizing the attainment of divinity.

This is further proof that sacred Greek has its roots in Sumerian.

íli” refers to the deification of the primordial father, the ancestor of humanity.

The second thing to understand about the meaning of the Greek illy, a transliteration of the Sumerian íli , is that this elevation refers to the elevation of primordial man, a human being, to the rank of god.

Why is that?

A god doesn’t need to BE ELEVATED or DEIFIED. He ALREADY is.

Because quite simply, the fact that a god needs to be elevated, carried, held, suspended, implies that this has not always been his condition. A true god doesn’t need to be elevated, to be put on high, because he already is and always has been.

This action of elevation thus indicates by name and literally the mythification (not to say mystification) that consisted in making mankind believe that the primordial man, after his death, had become the great divinity, the father of the gods. Thanks to the regenerative power of his wife, now a mother-goddess, and the new birth she gave him by returning to her womb.

The equivalence between god and the father, the ancestor, the eldest, the oldest

Sumerian Īlu and illu

It could also be argued that this god was the primordial human for another reason.

It is indeed very interesting to note the meaning of Īlu mentioned by Mr Michel, for whom it has, among other meanings, that of “god[19] ” (the Sumerian name for god is usually diñir or dingir ).[20]

Indeed, its homophone illu means “high water, flood”; amniotic fluid[21]

Now, deluge is a synonym for father, because “a” means “father” and also “deluge”[22] .

What does this tell us?

That he who has been raised to the rank of divinity by the rebirth wrought by the mother-goddess, by the action of her carrying him in her womb and into heaven, is none other than the father, that is, her husband and spouse.

Elamite “nab” for god

Elamite confirmation that the god is the father can be found in the fact that the word for god is nab.

Indeed, this name means ocean, being the contraction of (ní “fear, respect” and “aba, ab” “lake, sea)[23] .

This symbolic ocean, lake and sea should not mislead us, for they actually refer to the Sumerian “a” for “father”, which means not only “flood”, but also “water” (see note above).

The Sumerian counterpart to the Elamite “nab”: father, elder, ancestor

Moreover, it is abundantly clear that this aba, ab elamite is the counterpart of Sumerian:

Indeed, in Sumerian aba, ab designates just as exactly “a lake, the sea”[24] , and its homophone ab-ba … the father, the eldest, the ancestor [25][26] .

Please understand, then, what this means: that he who, according to mythological religion, was carried in his womb by the mother goddess, to be granted a new birth after his death, a rebirth enabling him to be raised and become the father of the gods, is none other than the human ancestor, the eldest father, in other words, the primordial man.

Now that we’ve understood the meaning of íli to understand the meaning of the Greek illy in Hera’s name illythia, let’s turn to the meaning of ti.

This will allow us to completely lift the veil on the true identity of this mother goddess.

ETYMOLOGY OF “Ti”, “Te

As we’ve already seen in our analysis of Eve’s name and the symbolism of the rib, the vulture and the mortar, the primordial mother who gave life to humanity bore the Sumerian name Ti and its synonym Te.

Let’s briefly recall why:

“Ti”, the rib, the side, the spouse, the companion, the arrow

Because she was drawn from Adam’s rib or side, and because the word side in Sumerian means spouse or companion, Eve was called Ti or Te, and the symbols used to represent her included a rib or an arrow.

The reason for this is that in Sumerian “ te, ti ” are strictly synonymous[27] and that they indistinctly designate “a side, a rib, an arrow[28] ” .

“Ti”, life, the giver of life

Because she is the mother of all living beings and the one who gave life to her children, humanity.

Indeed, ti, like tìla, tìl and also means “life”.

tìla is a contraction of “tu“, “to be born” and “íla“, “to raise, to carry”, and therefore literally means “to raise, to carry the being born”.

This of course ties in perfectly with Eve, whose Hebrew name (with the yod which can be transliterated “y“, “v” or “w”) transliterates “haya” or “hava” or “hawa” and comes from a verb of root HWH carrying the idea of “to live” or “to make live” or “to make become” and therefore meaning “the mother of the living” or “she who gives life”.

“Te”, The foundation of the world

Because as woman and primordial mother she is at the foundation of the world (te)

“te” refers to the primordial female progenitor, the woman who founded the world of gods and men.

In fact, it’s quite remarkable that the cuneiform sign “te” transcribes the words “temen, te-me-en or te-me“, meaning “foundation” . [29]

So “te” means foundation, which of course logically applies to the primordial mother at the foundation of the world.

On this subject, for those who still doubt that sacred Sumerian is the origin of sacred Greek, for example, simply consider that if each of these terms designates a foundation, if we add to them the logogram suffix “eš” meaning “anointed” or “tomb”[30] , temen- eš then takes on the meaning of “temple” of “sanctuary”[31] , being literally the foundation or holy perimeter, which is obviously the real origin of the Greek word for sanctuary “temenos“[32] which designates more specifically the sacred space dedicated to the divinity[33] .

“Ti, Tum, aka”: She who does, acts

Further etymological evidence links the primordial mother Eve to the logograms “ti,” “te”.

The fact is that one of its major Sumerian names, aka, in its verbal form, has the meaning of doing, acting[34] .

Now, if te, ti are equivalent and mean, in particular, an arrow[35]

the logogram tum, which also signifies an arrow, also signifies an action, a work[36] .

On this axis too, the arrow (te, ti, tum) is a symbol of the primordial mother Eve-aka as the one who acts, who makes.

This fits in perfectly with the fact that the Hebrew name Eve is built on the verbal root HWH on which the name of the true god YHWH is also built, with the meaning of the one who makes (himself) become.

A brief reminder of why the primordial mother under “ti, te” was associated with the vulture and the mortar.

As a reminder, the Egyptian goddess Hathor was commonly depicted with a vulture and a mortar[37] .

The same was true of Isis, with whom she was associated.

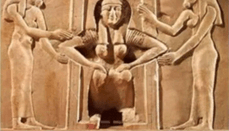

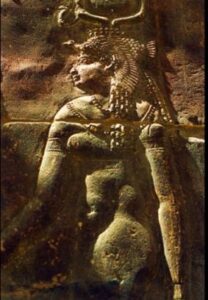

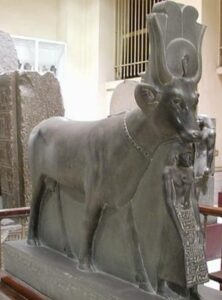

Here’s an image of Isis wearing the attributes of Hathor on a bas-relief from the temple of Isis in Philæ, dating from the Ptolemaic period, and next to it on the right is a representation of Hathor in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo:

In the case of Isis-Hathor, the vulture on her head, the mortar above and the horns of the Hathor cow can be seen.

Why the vulture?

There are two clear and simple axes associating ti, te with the vulture, one of the emblematic symbols of the mother goddess.

“Te”, the bearded vulture

A first direct axis is the simple fact that “te” simply refers to a vulture[38] .

This is one of the major reasons why this animal has been used to represent Eve and all the senses attached to her from ti, te.

Te, a side by its equivalence with Á, á.

A second, more indirect axis is that Te le vautour also means a side, a word we know to be associated with the primordial woman.

We can say that vulture also means a rib, a side, a spouse, a companion because the Sumerian phonetic equivalent of “vulture” is “ Á[39] ” or “á“.

Now, one of the primary meanings of “á” is: a side, an arm[40] , words which, as demonstrated in detail in the symbolism of the rib[41], have the meaning of “companion, support, spouse”.

direct association with the Vulture in Egyptian hieroglyphs

By the way, since we’ve just said that the Sumerian vulture has the phonetic equivalent Á, this is fully corroborated by Egyptian hieroglyphics, where the A is represented by a vulture.

Indeed, what do Egyptian hieroglyphs tell us about this?

The “simple”, fundamental counterpart is as follows:

A = Vulture [42]

It’s the very first letter of the alphabet, when presented in phonemes.

Let’s face it, it’s quite extraordinary to see that while Sumerian names a vulture “te” with the corresponding ideographic value ” Á “, Egyptian names the vulture ideogram “A” in reverse!

Or, to visualize it better, when the Sumerian tells us:

“te” = “foundation, vulture, mortar”.

= á” = “side, arm

(= “ti” = “rib or side” / “life” / “arrow” …)

The Egyptian tells us: Vulture = “á”!

We could say that we’ve come full circle, and we can immediately discern the close link between archaic Sumer and Egypt, in terms of linguistics, i.e. the sacred linguistics that dictate mysticism and religion.

For it can surely be no coincidence that in Sumerian, as in Egyptian, the symbol of the vulture has a phonetic “a” as its correspondence or equivalence.

This simple example is already, in itself, indubitable proof that these two sacred languages are closely linked in their symbolic expression.

In this respect, we might add that if Champollion had known Sumerian, he wouldn’t have had to grope his way through deduction to work out the phonetic meaning of vulture.

But we’ll come back to this later, as this Sumerian-Hieroglyph correspondence, beyond its mere linguistic equivalence, has far-reaching implications on a sacred level, and therefore requires a dedicated chapter.

Conclusion on the meaning of “te” the rib, the side:

If we return to our demonstration that “te” does indeed designate a rib, a side, we have seen that this is indeed the case, and through two distinct semantic axes:

- By its equivalence with “ti” (rib, side, arrow)

- By its cuneiform sign “Á” “á” (arm, wing, rib, side, horn, power)

This cannot be a coincidence.

Why a mortar?

Let’s take a brief look at why the primordial mother (goddess) was associated with the mortar.

We’ll confine ourselves here to an etymological consideration, as there is also a powerful symbolic reason.

Let’s just say that vulture and mortar are synonyms in Sumerian.

Indeed, if in Sumerian “te” means “vulture”, its homophone “tè” also means “mortar or enclosure” (due to the equivalence of “tè” with “naña[43] “. Indeed, tè designates an alkaline plant, soapwort, cardamom, just as the term “naña” designates, in addition to soapwort, a mortar, an enclosure, a circle, the whole [44][45] ). This enclosure, this circle, itself refers to one of the meanings of te, which, as we have seen, designates a perimeter, a foundation.

Conclusion on the relationship between “ti, te” and the vulture and mortar

Thus, the primordial mother because she was called ti or te :

- Ti, the rib, the side (the spouse, the companion), the arrow

- Ti, life, the giver of life, the mother of all living beings like Eve under haya, hava, hawa

- Te, the foundation, the perimeter, the sacred enclosure

- Ti, tum, aka (Eve) she who does, acts

Was etymologically associated with the vulture because :

- Te is a vulture

- Te is a side, because a vulture is also pronounced Á and á means a side, an arm.

Etymologically associated with mortar because :

- Te la fondation le périmètre has as homophone “ tè ” which is equivalent to naña meaning a mortar and an enclosure, a circle, the totality.

We can thus see the following symbolic linkage, associated with Eve, the primordial mother turned mother-goddess, since etymologically intertwined between :

- ti = rib or side (spouse, partner), arrow; life

- te = foundation, perimeter, enclosure or circle; vulture

- tè = mortar, enclosure

- Á, á = side, arm (spouse, partner)

ETYMOLOGY OF A

Having seen the meanings of íli and ti, we now turn to the meaning of a.

We have already mentioned that Á, á can designate a side, an arm, in the sense of spouse, companion (cf. the symbolism of the rib).

We also saw a little earlier in the analysis of illu that a in Sumerian designates the father[46] .

As a result, the final a can just as easily refer to :

- the primordial mother as the rib, the side, the spouse, the companion of the father

- the father (with the possible double meaning of father, partner, companion)

CONCLUSION ON THE DEEPER MEANING OF ILLYTHIE

Thus, under the veil of the Greek Hera Illythia hides none other than the primordial mother Eve (haya, hava, hawa) under her Sumerian names of ti, te or aka :

- Ti, the rib, the side (the spouse, the companion), the arrow

- Ti, life, the giver of life, the mother of all living beings like Eve under haya, hava, hawa

- Te, the foundation, the perimeter, the sacred enclosure

- Ti, tum, aka (Eve) she who does, acts

With their associated symbols, the vulture (te: a vulture, one side Á and á) and the mortar (tè, naña, mortar and enclosure, circle, totality).

A mother with the power not only to give birth to her posterity, and to her children, but also and above all to give life by a new birth to her deceased husband and regenerate him into the great male divinity.

Further proof of the link between Eve sous ti, te and sacred (re)birth: the enclosure!

By the way, if you think that the birth she performs is a completely natural birth and has nothing mystical about it like the rebirth she brings to those who pass through her womb, then please consider this:

We’ve seen that the primordial mother-goddess, symbolized by the vulture and the mortar, is also a foundation, a sacred perimeter; this gave the name temen-eš[47] from the Sumerian temple to the name of the sanctuary of the Greek temple temenos “[48] a term that more specifically designates the sacred space dedicated to the divinity[49] .

We’ve also seen that te (as a homophone of “tè“, which is equivalent to naña) means not only a mortar, but also an enclosure, a circle (hence a circular enclosure) and “totality”.

Now, as it turns out, the term “pregnant” has an extraordinary double meaning, which is highly revealing of the mystique it conveys.

In hieroglyphic, a pregnant woman is called bkAt [50] and the enclosure, as the foundation and floor of a temple, is called bkyt or bAkAyt[51] .

These two terms are excessively close, if not equivalent, as Ay, A and y are potentially interchangeable in Egyptian[52] .

It’s quite extraordinary that, etymologically speaking, the foundation of a temple, its sacred enclosure, is synonymous with a pregnant woman![53]

Even if the whole symbolism of temples is obvious (a symbolism which is examined in detail in volume 3 The Bible of Symbols, as well as in volume 6 on megalithic and historical temples), this etymology alone, in this case Egyptian, is eminently revealing of the fact that in mythological mysticism, the temple was envisioned and conceived as the very symbol of the body of the mother-goddess, to represent by its circular foundation the power of her womb not only to bear children, but also to confer a new birth on the father of mankind to make him a deity and, by extension, on all his devout children.

We can also add that it is then considered to be the foundation not only of the material world, but also of the spiritual world. This is why te also means totality. It is the origin of the whole world, and it is the whole world.

We will, of course, have ample opportunity to develop these various considerations elsewhere.

I won’t go into the etymology of the Egyptian bkAt here. I will do so separately, but in view of what has been said here, this word is easily decomposable (ba-akA-t) and allows us to identify the primordial pregnant woman who generated this word.

What we absolutely must remember and understand in the logic of this article dedicated to the analysis of the crouching mother goddess is that, indisputably, the crouching position of the mother goddess under her many faces and names was not only intended to represent classical human birth, but also had an eminently important figurative and sacred symbolic purpose, in that it served to represent her power to procure the rebirth of the dead in the afterlife. Sacred symbolism that was, no pun intended, used at the foundation of the temples.

We also need to understand that, because the symbols chosen to represent her are strict synonyms of Eve’s name or of her various appellations, the veil of identity of this mother goddess has already been lifted in this simple article.

To attest to the universality and timelessness of this representation, let’s take a look at some other examples of crouching divinity :

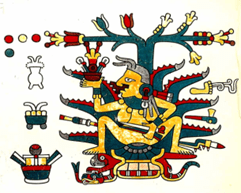

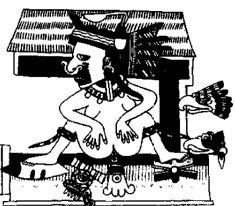

THE MAYAS

Here are some simple examples of crouching Mayan deities:

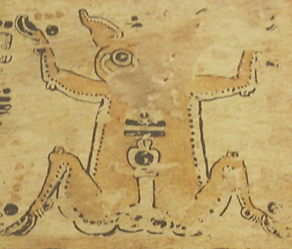

Figure 3: Madrid Mayan Codex

Figure 4: Madrid Mayan Codex

LAJJA GAURI FROM THE INDUS VALLEY

It is remarkable that this representation of the crouching goddess is both emblematic and ancient in India.

Take the example of the goddess Lajja Gauri:

Devi bhakta – Personal work

Note in passing that these legs form an M, as we’ll see later.

According to the Rig Veda, one of the 4 great sacred books of Hinduism, she is the symbol of the mother goddess who gave birth to the universe, both spiritual and material.

“In the first age of deities, existence was born from non-existence,

The quarters of the firmament were born from Celle, who crouched with her legs spread.

The earth is born of She who crouched with her legs apart.

And from the earth, the quarters of the firmament were born.”

Rig Veda, 10.72.3-4

Thus, from the crouching mother goddess are supposed to come heaven and earth, the entire universe.

However, it is important to understand that the power attributed to him goes far beyond the “simple” creation of the world, including the world of the living.

For the mother goddess in this form is not only the creator of the world. She is also presented as the recreator of the world.

The title of the book from which this source is taken refers to this: “creative and regenerative”.

This is also what we’ll see below.

Note that this mother-goddess and her representation in this form date back to the earliest antiquity, since it is drawn from the cult of the great mother-goddess Shakti or Devi of the Indus Valley[54] , whose earliest traces are dated by archaeologists to be over 8,000 years old.

Remarkably, both of these names are direct names for Eve in Sumerian.

Shakti en sumérien

For example, shakti breaks down into ša-aka-ti in sacred Sumerian:

- (if, as we shall see in the analysis of primordial man, ša can designate him) ša[55] means (also) the body, the womb! the middle, the inside, the intestines, the heart, the stomach, the abdomen, the bowels, the riverbed, the body fluids, a hollow vessel containing water or grain or urine and excrement; and its homophones sag9, šag5, sig6, sa6, ša6 means divine grace, good fortune, fertility[56] .

- a-ka means procreative mother, genitrix (remember that a-ka has the equivalent úgu[57] whose homophone úgu4 (KU) means to bear, produce, procreate )[58]

- ti designates with ti: “the rib, the side (the spouse, the companion), the arrow”; with ti equivalent to tìla, tìl: “life, the giver of life, the mother of all the living” as Eve under haya, hava, hawa; and with ti equivalent to tum, aka, their meaning of “she who does, acts”).

Afterwards, you can always come and tell us that :

“Shakti represents the feminine element of every being and symbolizes the cosmic energy with which it identifies. Shakti is usually closely entwined with Çiva, who represents the Unmanifested, the Father, while she is the Manifestation, the divine Mother. Experienced Çiva transforms into Shakti. But she must remelt herself into him, to regain original unity. Çiva and Shakti are one in the Absolute, the two aspects, masculine and feminine, of unity”. (CHEVALIER-GHEEBRANT, Dictionnaire des Symboles, 2005, p. 881)…

… But this so-called “cosmic mother”, incarnation of the eternal feminine, will fool no-one, or rather only those unable to lift the veil of appearances behind which lies the primordial mother of humanity.

If anyone doubts the link between sacred Sumerian and Sanskrit, and that “aka” does not refer to the primordial mother Eve, let me simply remind you of this simple fact (among a myriad of other examples that I’ll have the opportunity to cite when analysing the name Eve):

AKKA IN SANSKRIT

Here is what is meant by different variations of the Sanskrit root AK[59] :

अ A, in the monosyll. ôṃ, represents viśṇu.

अ क् A K. akâmi –) means to go tortuously, to wind; to act in a tortuous manner. Gr. ἀγής, ἀγϰύλος (agês, agkulos).

अक AKA –) n. sin, fault; ‖ grief, sorrow.

अक्का AKKÂ –) f. mother.

Akkâ in Sanskrit therefore not only means Mother, but also has a very clear contemptuous consonance in direct etymological association with tortuous action (which the Sanskrit akâmi designates), with fault, sin and the resulting sorrow and grief (which its Sanskrit homophone aka designates).

You have to admit, it’s strange, to say the least, that these notions of sin, fault, tortuous action, sorrow and grief should be semantically associated with a “cosmic mother goddess” depicted as the source of all neutral and absolute energy…

On the other hand, it obviously corresponds perfectly to the life events of the primordial human mother.

Once again, this is just one fiber in a steady stream of evidence, all of which I shall endeavor to enumerate.

Concerning the Sanskrit akâmi, let us note, in addition, as if that were not enough, that mí ” in Sumerian designates a female[60] , a cavity, something or someone black, dark[61] , just like its synonym kúkku whose homophone designates an ancestor[62] …

Where, frankly, is the astonishment that, because of her tortuous actions, our ancestor, the primordial mother, was put to death and then deified and represented as a chtonian divinity, the goddess of the world of the dead and reigning from the cavern, her womb, over it?

Sha-aka-ti is thus, in both Sumerian and Sanskrit, a perfect avatar of the primordial mother Eve and of the divine power attributed to her to regenerate her husband through “ša”, her womb, and by extension, all the dead, to the point where she was elevated to the rank of goddess of heaven and earth, at the origin of the creation and re-creation of all things.

A GROUP OF THE MOTHER GODDESS AND THE “CROUCHING GOD” AT THE AUXERRE MUSEUM

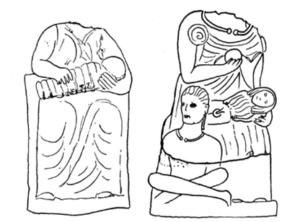

In France, a very interesting statuary can be found at the Musée d’Auxerre (see illustration on right below).

Fig. 1 – Mother goddess of Capua.

Fig. 2 – Mother goddess of Auxerre. Reconstruction.

OBSERVATIONS

It associates three figures: the mother goddess in a dominant position, with an apple of immortality in her right hand, a child on her lap and left arm[63] and her parèdre crouching beside her.

The author of the article I referenced, Mr. Benoit Fernand, states that this mother goddess is a Courotroph goddess (i.e. a nurse), associated with Ceres-Demeter and, indeed, with all mother goddesses, whatever their names, and that she is a personification of Nature, of Mother Earth[64] .

I’d also like to draw your attention to the fact that she is depicted without a head, like the Maltese mother goddess we examined in the article on solving the mystery of the Maltese temples, and other mother goddesses we’ll be discussing in the future. Indeed, we’ll be taking an exhaustive look at why the mother goddess has been universally depicted without a head in Volume 2.

I would also draw your attention to the fact that his parèdre is associated with a horned god and is represented crouching, to his left, in a position of inferiority[65] and also asleep, eyes closed, a sleep that evokes the sleep of death[66] .

Also note in passing that the child is depicted swaddled and is sometimes interchanged with a boar[67] . I will explain separately the sacred meaning of the symbolism of bandages (which refers to the symbolism of the goddess of ropes or the one who ties), as well as the symbolism of the boar in separate, dedicated articles.

As for the child, note that unlike the mother goddess’s parèdre, who is “asleep in death”, he is, to say the least, very much alive, since he is represented in the ithyphallic position[68] (i.e. with erect sex).

After these few essential observations, the question is: what does this scene mean? And, in view of the article we’re dealing with here, why is the mother-goddess’s parèdre here in a crouching position?

WHAT DOES THIS SCENE MEAN?

WHAT PREVIOUS RESEARCHERS THINK:

According to Mr. Benoit Fernand, the author of the referenced article analyzing this statuary, the child serves to represent (as etruscologist and archaeologist Jacques Heurgon had already suggested) not classical maternity, birth, but the deceased[69] , who is welcomed, upon his death, into her womb, into the bosom of Mother Earth[70] .

What reinforces this idea is his observation that in the case of the Tourettes-sur-Loup statue, the mother-goddess is holding a severed head on her lap in place of the child, over which she is placing her left hand[71] . From this, he deduces that the severed head represents the dead, that it is the double of the deceased, and that this is also the meaning to be given to the child[72] .

As for the fact that this representation of the mother goddess is linked to the rebirth of the dead, he mentions the French scholars Camille Jullian and Salomon Reinach, whose findings are interesting, at least in demonstrating that this type of representation is indeed about the rebirth of the dead.

Indeed, Mr. Benoit Ferand rightly points out that the mother goddess is the goddess of the world of the living, but also of the dead, and that as “guardian of the sepulchre she is the one who communicates life” [73]

He goes on to report that Camille Julian (who shared the views of Salomon Reinach, a proponent of an animist or totemistic reading of mythology and religion), not only saw in it “the personification of ‘Mother Earth'”, but “was not afraid to assert that it was ‘supposed to re-engender the dead‘”: “hence”, he said, “the crouching position of skeletons”[74] .

THE TRUE MEANING OF THIS SCENE

To fully understand this scene, we need to put things into perspective and graduate the different levels of symbolism.

While it’s fair to say that the mother goddess depicted in this way serves to indicate that she is the mother goddess of the world of the dead and has the power to regenerate them, there are also many errors to be corrected.

The mother godess : the primordial mother, not a hypostasis

It is in fact false to say, as we systematically read from supporters of an animist or totemic or shamanic vision… that the mother goddess is merely a hypostasis of the Earth, i.e. a personification of the Earth made into a goddess by primitive populations (i.e. less cognitively endowed than us Westerners…).

Indeed, we’ll have ample opportunity to demonstrate – and this article will be just one of a thousand – that the sacred Sumerian and hieroglyphic languages on which the divine names and symbols of mythology are based, and which enable us to grasp their exact meaning, indisputably demonstrate that the mother goddess is, in fact, a very real character, no more and no less than the primordial human, Eve, who was deified mother-goddess of the Earth and the underworld. That she was quite simply the first of the gods, the deified ancestors! And that it was to her that the power to regenerate the dead was attributed.

Indeed, we shall see exhaustively that, not only has she been expressly and directly named under her various names under all the heavens, but that absolutely every event in her life is recounted in mythology (and the same goes for the primordial man, Adam…; for the events part, volume 2 will demonstrate this vividly).

What prevented all these eminent authors, like so many others, from seeing and understanding this was, it has to be said, among other things, their linguistic specialization, which in terms of ancient languages was often limited to Greek or Hebrew, which are in fact, from the point of view of linguistics and history, very recent languages and certainly not those on which all sacred symbolism is based. This lack of knowledge of the essential languages of Sumerian and Hieroglyphic necessarily led, by rebound, to their lack of understanding of symbolism, of the meaning of the symbols that are the keystone of mythological narratives. And without an understanding of this symbolic language, it’s impossible to access the very real story that myths tell, or the nature of the religion they preach.

But let’s return to the meaning of this representation:

A first-level reading: the triad

Above all, it’s absolutely essential to understand that the son in the mother-goddess’s arms is, before anything else, the reincarnation of his dead parèdre, husband, spouse, the very one crouching at his feet.

The first meaning of a child is not that it represents the deceased, in the sense of any deceased person.

For the deceased is first and foremost the father of the gods, his godfather.

And in this representation, the deceased is the crouching parèdre.

The child does not represent the deceased, the dead godfather, but what the godfather will be; it designates the regenerated godfather, when he returns from the world of the dead.

The message being: I am the almighty, and by the power of my womb, I can restore life to my husband and spouse, to the father of the gods who was put to death, and restore life to him in the form of our son whom he himself begat me before his death.

It’s no more and no less than the great classic triad we face : father, mother and son, reincarnation of the father.

The fact that the child is in the ithyphallic position serves to indicate not only that he is alive, but that he is the father, for, as we shall see, the father of the gods was regularly represented in the ithyphallic position to indicate not only his status as the father of humanity, but also, in his specific case, his ability to impregnate the mother and thereby give himself a new birth.

As for the fact that the child is sometimes substituted by a skull, this also serves to indicate that she has the power to restore life to the dead father of the gods. In all cases, whether child or skull, they both refer first and foremost to the father of the gods, either regenerated in the case of the child, or in the process of being regenerated in the case of the skull. In connection with the presence of a skull, it’s also very important to know and understand its symbolism, which is a microcosm of the cavern and points directly to the womb of the mother goddess, from which she brings forth, or reemerges, the world. This skull therefore goes far beyond the simple symbolism of a lambda deceased person.

A second-level reading: the message to worshippers

Secondly, it’s true that this representation also conveys a clear message to the pagan worshippers of this triad, no more and no less: a promise of immortality.

For what the father has experienced is a promise to his worshippers that they too will experience the same thing, provided they recognize the power of the mother goddess and worship her.

The message being: you see, just as the mother goddess matrix did for the father of the gods, it has the ability, the power, to regenerate you too when you die.

Hence the apple of immortality she hands them…

The same one she seized in her own time, believing in the same promise that had been made to her…

But this message, addressed to the worshippers who see the scene (to the “lambda deceased” one might say), it is important to understand, is a second-level meaning.

And in the case of worshippers, the child does not represent the deceased worshipper either, what he is, but again what he will be once he returns from the realm of the dead; he represents what the deceased may aspire to become, that is, he too, a born again, aspiring, like his ancestor, to divinity[75] .

THE REASON FOR THE CROUCHING OF THE FATHER OF THE GODS

As for the crouching, it’s fair to say that the crouching position of the father of the gods on the left and below the mother goddess symbolizes his dependence on her.

This scene clearly shows that the power of redemption and regeneration granted to the mother goddess helped give her a pre-eminent role. Even if, whatever supporters of the matriarchal cult may think, this in no way implies the absence of a patriarchal cult, as we shall see, since the two coexisted, feeding off each other. Benoit mentions, for example, the case of the crouching goddess of Besançon, who combines matriarchal attributes (crouching, cornucopia) and patriarchal ones (Cernunnos deer antlers).[76]

If we are to understand the meaning of the crouching position of the father of the gods, we need to place it in the overall context of this representation, whose central theme is, as we have seen, the teaching of rebirth of the dead through their return to the womb, the womb of the great goddess his wife.

Thus, crouching, whether when the mother goddess is crouching, or when the father of the gods is crouching, always has a connection with expressing the regeneration of being through the mother goddess’s womb and, as we’ll see later, a connection too with fluid symbolism.

In the case of the crouching father of the gods, two different meanings can be identified:

- When the father of the gods is depicted crouching in a dominant position, it’s to signify that, because he has succeeded in becoming a great divinity, he is just as likely, like the mother goddess, to communicate to the living and the dead, through the gift of his fluids or humours, abundance on earth and immortality in the afterlife. We’ll see this a little further on, with the example of Cernunos and the Mayan gods.

- When the father of the gods is represented in a weak position, as he is here, in a state of sleep symbolizing death, it’s to represent his foetal state. He is dead, and must go through a gestation process (which I’ll detail in a separate article) before he can claim rebirth.

This latter case is in line with the explanation given by Camille Jullian (referenced above) that the deceased were placed in the foetal position in the tombs to signify their rebirth to be provided for by the mother goddess.

Here’s an interesting example to follow :

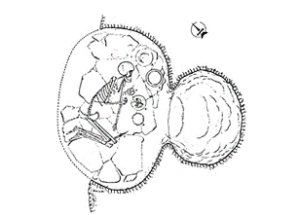

THE PREHISTORIC SITE OF THARROS IN SARDINIA WITH A DECEASED PERSON CROUCHING IN THE FETAL POSITION, HOLDING A STATUETTE OF THE MOTHER GODDESS STEATOGYPE IN HIS HAND FACING THE FACE.

At the Tharros site in Sardinia, in one of the hypogeic tombs (i.e. an underground crypt or burial site), there is a “deceased person crouching in the foetal position, holding in his hand, pointing towards his face, a statuette of the Mother Goddess steatopyge[77] “.

But what nobody says – and apparently, nobody sees! – is that the tomb itself was designed to represent, if not the local mother goddess, at least her womb, into which the deceased was then placed.

Just look at this sketch of the archaeologist’s survey of this tomb:

Fig. 2 – Neolithic tomb at Cuccuru S’Arriu (second half of 4th millennium BC) (Archaeological Superintendence Archive)

The deceased was literally placed in the foetal position in a burial site that was also shaped like a womb!

This should come as no surprise to us, given the analysis of the megalithic temple at Göbekli Tepe, for example.

The underlying concept, of course, is that the deceased and the society that prepared him were absolutely convinced that his death was the prelude to his rebirth, thanks to the regenerative power attributed to the mother goddess’s womb.

A ÇATAL HÖYÜK

To attest to the age of this representation, we can also cite the following source:

“In Çatal Hüyük (Anatolia-Turkey) in the 1960s, archaeologist James Mellaart unearthed a number of statuettes. The female body is depicted in the birthing position, above bull skulls. For the archaeologist, these “sanctuaries” and statuettes reveal the existence of an original cult, paid to a divinity who created life and death. Founded on the concept of regeneration, this cult is said to have endured in Greek myths, making Anatolia the cradle of Western civilization. This discovery gave rise to the idea of a religion in which the female body embodied both the “Mother Goddess” and Mother Earth, and, more broadly, a divinity that created life and death[78] .

So, in a site as old as Çatal Hüyük in archaeological terms (dated between 7,100 and 5,600 BC), the mother goddess is again and again found in the birthing position, representing her power to bring life back to the dead.

The presence of a bull’s skull, one of the symbols of the father of the gods, indicates once again that the first object of this regeneration was her own husband.

THE SYMBOLISM OF THE GREAT CROUCHING DIVINITY AND THE SYMBOLISM OF VITAL FLUIDS

Having understood that the crouching position assumed by the mother-goddess represents her omnipotence over the world of the living and the dead, being a symbol of her status as mother-goddess not only of birth, but above all of the rebirth of the dead (with, foremost among them, her husband, the father of the gods reincarnated in the son-god), we will now take a brief look at another symbolism closely associated with the crouching position: that of vital fluids.

Let’s not forget that the symbolism of vital fluids expresses the mythological doctrine that all the vital fluids of the great divinity – urine, sweat, excrement, etc. – are the fruit of his body and flesh, just like his son, and are therefore true and perfect substitutes for this redeeming son-messiah.

Thus, in mythological paganism, mystically, drinking the urine of the great divinity, drinking his menstrual periods, feeding on his excrements, etc. was a ritual performed as a veritable Catholic transubstantiation supper, even if eminently pagan in nature, since in the minds of devotees it amounted to symbolically eating the flesh of the messiah son and thereby benefiting from his power of redemption synonymous with immortality.

Indeed, because the mother-goddess gave him life, and, as we shall see, because the father of the gods is also the progenitor of the promised pagan redemptive son-messiah, consuming the fruit of the flesh of the bodies of the great deities, whether mother or father, will be seen as a direct means, like elixirs of fertility and immortality, of obtaining abundance in earthly life and immortality, divinity in the afterlife.

Concerning the ability of the Father of the Gods to give his bodily fluids, which is an attribute generally associated with the Mother Goddess, it should be noted that the Mother Goddess is most often represented for two reasons:

Firstly, because it is of course a major player in the process of gestation and rebirth.

Secondly, by feeding on the fluids of the mother goddess, the worshiper symbolically feeds not only on the mother and son, but also on the father (since the son is the reincarnation of the father). In other words, the worshiper feeds on the whole triad.

However, as we shall see, it is also possible that the father of the gods, or even the son deity, is sometimes represented in isolation, standing or crouching, giving his fluids, since both may have been given the power to produce abundance and immortality, either directly or through a doctrinal shift.

If we now return to the representation of the crouching mother goddess giving birth and/or diffusing her fluids, here’s what A. Parks says in her book (which aims precisely in one of its notes to explain the hidden meaning of menstruation in ancient cults ):[79]

This is why an extraordinary number of figurines depicting the Mother Goddess, usually in a crouching posture, are regularly unearthed all over the world. As the moon influences the female menstrual cycle, it is, in this very particular respect, also a related symbol of the Mother Goddess. (A.PARKS, The Secret of the Dark Stars , 2005, pp. 201, 203).

This is also why the priestesses of the Mother Goddess were often sacred prostitutes, reputed to transmit the sacred vigor and royalty of the Mother Goddess to future kings and princes[80] .

He’s absolutely right.

The rite of drinking one’s menses, or more broadly, the fluids flowing from the body of the mother goddess, was undoubtedly a major sacred rite.

Let’s take a look at some Mayan examples that illustrate this very well:

THE MAYAS

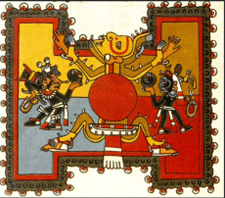

Here is a figure from the Codex Borgia:

Figure 5: Codex Borgia

This figure has the advantage of being unambiguous.

Indeed, it’s obvious that the great deity is pregnant with this red circle on her belly.

There’s an association between her crouching position and childbirth, especially as she’s obviously reached full term.

With the crouching position, we’re still talking about childbirth, the culmination of the gestation process.

In addition to this basic understanding, we can add that fluid symbolism here is directly linked to the crouching position.

Why?

Just note that while the belly is shown in red, the scarf is also shown in red and runs straight down from the belly, ending with bangs.

Here’s another enlightening figure:

Figure 6: Borgia Mexican Codex, plate 74[81] .

You’ll notice, firstly, that the large deity is in a crouching position and, secondly, that a hand with an eye or circle inside (similar to an inverted Fatma hand) is in direct extension of the large deity’s spread legs, just like the fringed red scarf in the previous figure.

What is the purpose of this scarf or inverted hand coming from in direct association with the vagina of the divinity above, about to give birth or in the birthing position?

It is important to understand that this scarf with its bangs, or this hand when inverted, represents the fluids flowing from the mother goddess’ womb.

Why is this so?

Let’s turn to another illustration of a Mayan divinity, that of the Mayan mother goddess, Ixchel.

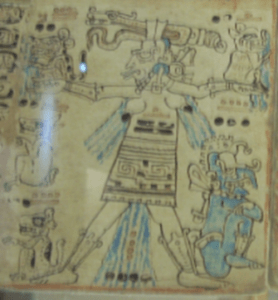

Figure 7: Madrid Maya Codex, plate 30 [82][83]

Ixchel, or Ix Chel, is the great Mayan mother goddess.

In glyphic texts, it is called “Chak Chel”.

Brief Sumerian etymology :

In Sumerian, Chak Chel can be broken down into ša-ak ša-el, i.e. the body, the womb, “ša“[84] from “ak(a)” the “procreator, genitrix”, which we know to be a name of Eve[85] and “ša” “el” the body, the womb of “a/el” the “raised father”.

You’ll notice that in this image from the codex, she has her arms and legs spread wide[86] and is spreading all her bodily fluids (milk from her breasts, sweat from her armpits, fluids from her vagina, but also her urine and excrement balls…).

You’ll tell me that in this imagery she’s not in a crouching position, but note: all the deities she’s associated with are.

It’s important to understand that, among the Maya, there’s a direct link between the crouching position of the great mother goddess, a divinity representing gestation and childbirth (which we know will lead to the birth of the son deity, reincarnation of the Father and endowed with redemptive power), and the symbolism of the fluids flowing from her body.

Here, too, are similar examples of large male and female deities associating the crouching position with the production of vital fluids such as elixirs.

Figure 1 image taken from the Mexican Codex Laud.

This figure depicts a horned God crouching in front of a turtle under a tree, emitting drops into a container.

Note that the Tortoise is right in front of the crouching deity, thus associating the Father of the gods with this attitude, but also the mother goddess since the Tortoise is one of her emblems[87] .

The other obvious association is the fact that the great deity is crouching as she collects fruit from her tree of life, which she then presses into an elixir of immortality.

So there’s an analogy between crouching and the production of immortality fluids.

But we also know that the tree is, among other things, a symbol of divinity itself[88] .

In other words, the tree from whose fruit the deity here extracts an elixir-like liquid of immortality is nothing other than his own body. It’s a way of saying that he has immortality inside him, and that he can extract it and give it to whomever he wishes.

Please also take a look at this other illustration:

Figure 2: Codex Borgia

Note that, with this other horned deity, the association between the crouching position and fluid collection can also be seen in this figure, with the small, cup-shaped altar between the legs of the great deity, clearly used to collect her bodily fluids.

What we have just said and seen, for example, helps us to understand the rock paintings of the Australian Aborigines:

Take, for example, the identical representations found in Aboriginal rock art:

Figure 8: Koala rock art Aboriginal rock art, Anbangbang rock shelter, Kakadu National Park, Australia

(According to ozoutback.com.au, it shows Namondjok, an ancestor of creation, with his wife Barrginj below, lightning man Namarrgon on the right and men and women in ceremonial headdresses below).

Figure 9: Petroglyph of the goddess Kunapipi, a traditional Aboriginal goddess from the Nourlangie Rock site in Kakadu, Australia, one of the oldest Aboriginal sites.

What are we seeing?

That the great god and the local mother goddess are both depicted in a crouching position!

What for? To give birth?

This cannot be the case with the Father of the gods

Here, they are factually both depicted in the birthing position, used to signify that as primordial father and mother and source of life and progenitors of the hero son-god with saving power, they bring life, fertility and immortality through the gift of their bodies and vital fluids to their worshippers by means of their local priesthood.

Here, too, it’s a ceremonial and sacred rite.

Let’s now look at other examples of how the father of the gods can be associated with the crouching position and/or the giving of vital fluids:

CELTIC WITH CERNUNNOS

The god Cernunnos (or Karnonos[89] ) is considered a true dis pater[90] .

We’ll have a chance to demonstrate that this is yet another face of the primordial, divinized human ancestor.

We can simply point out that he is represented as a stag god, since Cernunnos is depicted with a large stag antler and his Irish avatar, Nemed, is a stag god[91] ; that he is associated with Geyron, Trigaranus with their horned deity symbols, under the ox or bull.

Cernunnos on the Gundestrup cauldron Wikipedia at Cernunos

Goat horns, torque, ox, cornucopia and seated cross-legged posture of the Celtic god Cernunnos, Reims.

Some have thus associated him with Shiva, and deduce a probable mythological kinship between him and Shiva[92] .

What interests us in this article is that he is often depicted naked, cross-legged or in the lotus position[93] , while also frequently being directly associated with the mother goddess and holding a cornucopia[94] .

In our analysis of the horn of plenty, we have shown that this symbol, at the junction between the symbolism of the horn and the cup, the vase and the symbolism of the goat, is an eminently matrix symbol, representing the matrix in this case of the mother goddess.

So we understand why this god with a cornucopia is directly associated with the mother goddess.

Because this horn represents her womb. It represents her directly, as if she’s there, legs apart, in the birthing position, and the fact that he’s sitting cross-legged simply serves to recall the crouching position of the mother goddess when she gives life and when, mystically, she pours out her vital fluids from her womb onto the world, giving it abundance in the material world and immortality in the beyond.

It’s particularly interesting to note that this mother goddess, whose origins are obviously much older than Celtic, is a primordial goddess, ruling over the world of the living and the dead.

In fact, she is directly linked to Demeter, Cybele! and qualified as the goddess of the earth or Mother Earth.

Not only that, it is also linked to Neolithic female divinities[95] !

We’ll see that these observations only corroborate one of the facts demonstrated in my works, namely that all mother-goddesses are in truth mere multiplications of the same original divinity.

These simple observations, made by others than myself, help us to understand, at least a little, the universality and timelessness of the cult that was devoted to him.

I must add, of course, that my research will not only demonstrate this fact, but will go much further.

They will enable us to understand, at last! one absolutely essential thing: not only that all Mother Goddesses are variations or multiple faces of a single original Mother Goddess, but also, and above all, that Mother Goddess is not a mishmash concept of Mother Earth, an impersonal deity, a material Earth having been deified and made a person or character by humans a little less primitive than their fathers, who had begun to build spiritual concepts from natural observations (which is the scientistic postulate).

No, on the contrary, it’s about understanding that this original mother-goddess was, at the origin of the human world, a very real person, none other than the primordial mother of mankind, Eve. A primordial mother who was deified as, among other things, goddess of the earth and the underworld.

We need to understand that this is not an object made into a woman, but the opposite extreme, a woman made into an object, an object of adoration.

But let’s take a look at other examples of crouching deities associated with fluids:

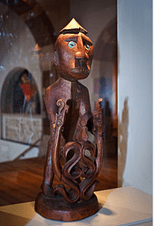

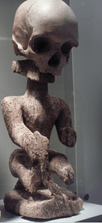

IN OCEANIA WITH THE KORWAR

As another example of this representation of the deity in a crouching position, I invite you to take a look at the sacred statues from New Guinea called Korwar.

First of all, it is worth mentioning that, by the very admission of the natives who venerate them, they serve to materialize or represent the souls of the ancestors who reside there, the spirits who have been elevated to the rank of divinity[96] and who then remain on earth to continue to serve as guides for the living[97] .

This is, of course, yet another illustration of human mythology, which has consisted in divinizing ancestors, which necessarily implies, first and foremost, the primordial ancestor.

What’s interesting to note in the context of this article’s analysis is that he is shown in a crouched position, knees and elbows bent, with an openwork screen between his hands, which, depending on the observer, represents a tree of life or the snake’s moult, which are designated as symbols of rebirth.

Korwar at the Trop enmuseum & Korwar statuette from Papua (Indonesia), Cenderawasih region

Photo credit: Hiro-Heremoana – Own work

In addition, the korwar consists essentially of a skull because of its exaggerated shape compared to the rest of the body[98] .

Source photo : Clock – Personal work

An exceptional korwar is preserved in Paris (Musée du Louvre, Pavillon des Sessions): its head is not represented, but is made from a real human skull. He must have been a very powerful chief, hence the honor of having preserved his real head and not carved it.

This is symbolism:

- of the door or doorframe (the openwork screen) representing the entrance to the matrix of the mother goddess,

- or even to the symbolism of the cup, which has the same meaning,

- the W’s association with the serpent, itself associated with the original tree of life, and the proposal to feed on its fruits/fluids, symbols which both hold out the promise of rebirth after death, of immortality, for the worshippers of this ancestor-turned-deity, the same immortality that he is reputed to have attained, and who thus remains on earth to show the way to his own kind.

Remarkably, his crouching position is intimately linked to the contextual idea of rebirth expressed by all the figure’s related symbols.

We might add that the fact that he holds a frame in front of the living is an explicit invitation to enter the matrix and feed on the fruits of the tree of life, mystically represented by the vital fluids of the tree-mother goddess.

THE AVARS OF THE MIDDLE AGES (PRESENT-DAY CZECH REPUBLIC)

If we remain on the level of documentary fleshing out of this imagery of crouching goddess = diffusion of bodily fluids, and in order to understand now how absolutely timeless and universal this principle of esoteric religion is, we can further illustrate it with another example closer to home.

After that, we’ll move on to examples that go much further than anything we’ve expressed so far.

This example, closer to home, was the subject of a very recent article in Géo magazine, echoing an article published on the ScienceDirect website . [99]

It relates to the discovery of exceptionally well-preserved belt buckles from the early Middle Ages, bearing the “mysterious motif of a reptile and a frog”, found in several regions of Europe, and which observers believe suggest the existence of a medieval cult, hitherto unknown to historians, practiced by various populations, including the Avars.

Here’s what we’re told:

When it was discovered near the village of Lány (South Moravia, Czech Republic), archaeologists thought it was a unique decoration: a belt buckle from the early Middle Ages, bearing the fascinating motif of a “dragon” (or simply, a snake) devouring a frog. However, since its discovery twelve years ago, they have learned that other curious artifacts of this kind have been unearthed elsewhere in the country, as well as in Germany and Hungary.

A study was therefore carried out on these objects which, although identified hundreds of kilometers apart, show great similarity. The results, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science in January 2024 and reported by Masaryk University in Brno, highlight the existence of a hitherto unknown medieval pagan cult. It is thought to have been shared by various populations in Central Europe before the arrival of Christianity.

Fig. 1: Overview of the belt ends examined. A) Lány (CZ), B) Zsámbék (H), C) Iffelsdorf (GER), D) Nový Bydžov (CZ).

For the authors, it was a motif that “linked the various peoples on a spiritual level”.

The article goes on to say that the authors of the study cannot confirm what the image of these buckles, the “reptile” catching its prey, actually meant to those who wore them. They note, however, that pictures of confrontations involving a dragon or snake are common in pagan rites.

The battle scene was an ideogram representing an unknown, but clearly important, cosmogonic and fertility myth, well known to various early medieval populations of different origins, they write.

“The motif of a serpent or snake devouring its victim appears in Germanic, avaricious and Slavic mythology. It was a universally understandable and important ideogram,” explains Jiří Macháček, head of the Department of Archaeology and Museology at Masaryk University’s Faculty of Arts. “Today, we can only speculate about its exact meaning, but in the early Middle Ages, it connected the various peoples living in Central Europe on a spiritual level.”

Especially since the famous Slovakian Ore Mountains, from which the copper ore used to make the belt buckles came, were located… outside the heart of the Avar khaganate.

These mysterious objects thus reveal a dense network of communication – perhaps cult-motivated, the experts suggest – in the Carpathian basin and beyond. “The analysis […] confirms long-distance contacts between Avar and non-Avar elites across Central Europe.”

What’s extremely laughable from the point of view of the symbolism developed in these articles, when, as we have seen, it’s proven that the mother goddess poured her fluids over the world in her position of (re)generating the world, is the fact that this frog is presented as such, the serpent-dragon as well, and above all that this serpent would devour the frog.

However, there’s no question here of devouring the frog, which is one of the animal emblems of the mother goddess (cf. the symbolism of the frog, notably the Egyptian examples of Heqet, the god Noun and his goddess Nounet).

Just look at the picture:

I’ll enlarge it for you:

Image C) Iffelsdorf (GER) enlarged.

I’m sure you’ll agree that you’d have to be pretty blind not to see that this dragon-snake is strangely grabbing this frog in the universal crouching position by… its genitals.

Clearly, this representation is not about devouring in any way, but rather about the fact that the snake, which is a symbol of the great original evil deity, but also of rebirth and immortality, indicates the means to access them, namely by feeding on the vital fluids emerging from the womb of the mother goddess.

It’s a way of inviting his pagan worshippers to celebrate this rite in the following way: if you want to be immortal, here’s what you need to nourish yourself at the source, for there lies the source of all life at the origin of the world of the living and the dead.

In the light of everything we’ve already seen, we couldn’t be more explicit in illustrating this belief and the rite that accompanies it.

THE MOTHER GODDESS ATAGEY OF THE ARAWAK CULTURE IN AMAZONIA

To better understand this representation of the Avars, and as further proof of its universality, we can turn to the example of the Arawak mother goddess Atagey[100] :

Photo credits: @botanical.sorcery #storiadellarte #arthistory #histoiredelart #medievalart #petroglyphs #portorico #medievaltattoo #mittelalter #godess #anthropologie

Note in passing that she is depicted as an old woman with her eyes closed.

And, above all, as specified in the reference quoted (it’s not me who says it!) that its legs are similar to frog legs…

Having understood through these different examples (Mayas of South America, Aborigines of Australia, Celts of Western Europe, Melanesians of New Guinea, Avars of Central Europe, Arawaks of Mesoamerica) taken from different continents and different periods the universality and historical timelessness of this representation, belief and practice, let’s now turn to its roots in prehistoric times:

AN EXAMPLE FROM THE UPPER PALEOLITHIC: FONTAINEBLEAU (France)

Here’s what you can see and read about it in the article: Une ” Origine du monde ” préhistorique à Fontainebleau published in Le Monde on 26/10/2020 :

In a sandstone shelter, a hydraulic system was partly created by man and dates back to the Upper Paleolithic:

Here is the image in question:

The three deep cuts, partly man-made in the Upper Paleolithic, surrounded by two horses. EMILIE LESVIGNES

Between Nemours and Étampes” … “Many millennia ago, these sandstone chaotic features, rising out of a cold, treeless sea of sand, attracted our distant ancestors to another activity: engraving. Today, there are no fewer than 2,000 rock shelters in the area that bear the imprint of prehistoric humans inscribed in stone. Most of these engravings date from the Mesolithic period, 9,000 years ago, the work of the area’s last hunter-gatherers. All we see are geometric figures, alignments of lines, grids, more lines…

And yet, in the midst of this weary repetition, there is a much older figurative exception, left by the ancestors of these ancestors.

It’s a heavy block of sandstone at the heart of which are two thin, natural, parallel gutters. Immediately to the left of the entrance, the wall forms a small panel where two horses, one highly eroded, the other much more complete, frame an intriguing figure composed of just three deep cuts that evoke a woman’s pubis with a vulva in the center and can be translated into three typographical characters: \I/.

On the right-hand side of the panel, a natural crack in the rock has been enlarged to evoke a hip and upper thigh. On the left, the fork in the wall, which slopes towards the entrance, plays the same role. If you step back – which is difficult when you’re on all fours in a narrow gallery – you can see a kind of prehistoric, minimalist Origin of the World.

Chance and bad weather: there’s no way of knowing the age of the engraving by instrumental methods, but it’s not necessary, explains Boris Valentin, professor of prehistoric archaeology at the University of Paris-I: “In its disproportions and mode of treatment, the complete horse has all the stylistic characteristics of what can be seen in the Dordogne at Lascaux or in the engraved Gabillou cave”. The “Lascaux school”, to use Boris Valentin’s light-hearted expression, means the Upper Paleolithic and a representation dating back over twenty millennia.

“After heavy rain, I moved to the shelter. The ‘vulvar slit’ was running.”

This engraved panel has long been known, but the beauty of science is that it never ceases to re-examine its objects. The engraving was keeping a secret, and its discovery owes something to chance and bad weather, as geologist Médard Thiry, a former researcher at the École des Mines, who brought his intimate knowledge of Fontainebleau sandstone as a gift to the archaeologists, recounts: “On January 23, 2018, after the rains that had caused the Seine to flood, I went to the shelter. The ‘cleft vulva’ was flowing. It was really gripping and, from then on, I set out to understand whether this flow could also be induced on demand.”

But how? Médard Thiry had his own idea. He had noticed that, in the upper passage of the shelter, which runs parallel to the first, but higher up, some ten centimetres behind the engraved wall, there were two depressions in the rock. These were two natural basins where rainwater accumulated as it entered the gallery.

“We changed the geometry of one of these basins to deepen it, to free up and probably widen cracks in the rock below,” notes Médard Thiry. The geologist and a team of archaeologists meticulously analyzed even the tiniest fissures on the site, as well as the deep lines that make up the two sides of the “pubis”. These were clearly dug out by one or more human hands, and small traces of punching and removal still indicate that the rock was struck to widen the two lateral features. The aim? To lead water seeping into the porous sandstone towards the central slot.

To prove this, the researchers carried out the experiment themselves, described in a study published in the October issue of Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. For a week, a simple reservoir and valve system supplied water to the basin, automatically maintaining a constant level as the liquid penetrated the rock. Water doesn’t travel through sandstone like that,” explains Médard Thiry. It has to wait until all the pores in the rock are saturated, and only then does it descend and concentrate on the lower part. In our experiment, we used around fifty liters of water and, after two and a half days, the vulvar fissure was flowing…”

Hydraulic engineering :